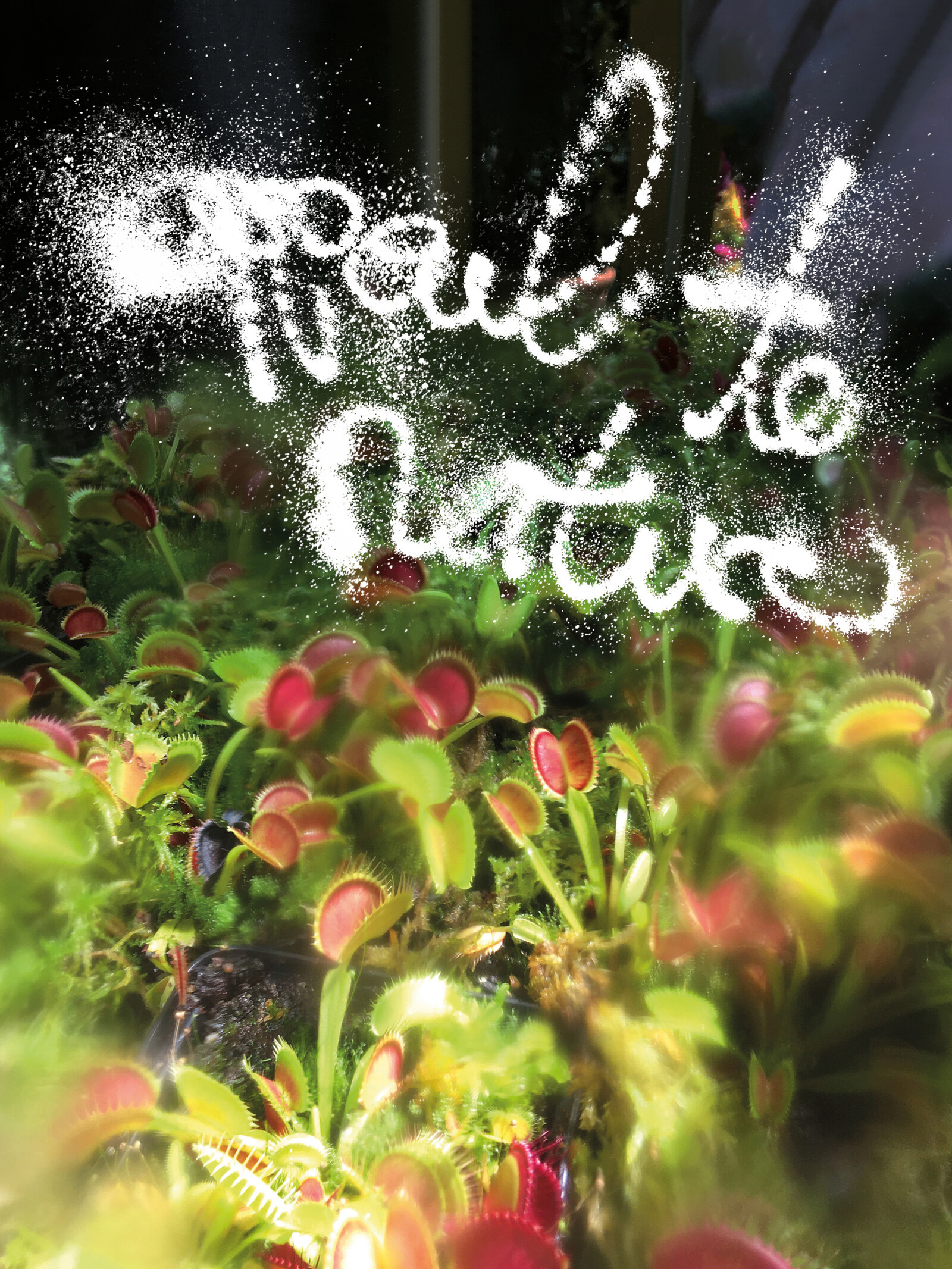

Carnivorous plants are a bit of a letdown. Far removed from the malicious, flesh-craving floral anomalies of my imagination, they are in fact quite benign. You can even buy them at the local hardware store. Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann’s series Carnivores however, allows the plants to shine without banking on any false expectations. Dripping with desire, they radiate a charm that has no need for exoticism, precisely because they put their own awkwardness on full display.

Appeal to Nature invokes catastrophe. The light that falls through the blinds, onto the glossy surfaces of the Carnivores, is no reminder of a friendly, nourishing sun, but of searing heat – the emissary of climate change. While there is certainly unease about the great calamity we got ourselves into, a sense of curiosity seems to linger in the room. In pleasant anticipation, Appeal to Nature awaits all the crazy stuff that is about to go down, all the futile attempts, improbable technologies, and desperate ideas to salvage what is beyond repair. Is it wrong to be just a tiny bit excited for disaster? At any rate, allowing yourself to feel this excitement would require stepping outside of the mental space that was assigned to us by the anthropocentric tradition of “western” philosophy of nature – a tradition that currently seems to be caught up in grief over a dying planet.

We think of nature as that which exists beyond our influence. We are told to look up to her, admire her, treat her with respect. In rhetoric, an appeal to nature claims that something is good because it is natural. In Frohne-Brinkmann’s work, nothing ever pretends to be natural. It is almost as if he doesn’t really care about nature. Carnivores is ostensibly not concerned with giving accurate representations of real plants. On another level though, the work is fascinated with nature and the value we assign to natural things. The series titled Roach Retreat shows cockroaches with a technological augmentation that makes them remote-controlled. Frohne-Brinkmann encountered them during his stay in Mexico City, an area prone to earthquakes, where cyborg roaches such as these will soon crawl the rubble in search for survivors, lending literal truth to Donna Haraway’s claim that cyborgs are our new ontology. In her famous Cyborg Manifesto from 1985, she also declares that, with the emergence of cyborg politics, nature and culture would no longer have to be divided. As if to test the merits of her propositions, Roach Retreat offers cyborgs a seat by the swimming pool. The composites recall David Hockney, who in 1982 similarly compiled pictures of naked bodies at a pool, cut up in squares by an instant camera, only at that time they depicted human males.

Nature puts us in a double bind. On the one hand, we feel obliged to finally meet her with the appreciation she deserves. On the other hand, this sentiment might just be what put us in this mess in the first place. As Timothy Morton has it: “Putting something called nature on a pedestal and admiring it from afar does for the environment what patriarchy does for the figure of woman. It is a paradoxical act of sadistic admiration.” Maybe the devoted worship we’ve been extending to nature ever since humans moved into cities was merely an act of lip service, reconciling us with the tragedy of the Anthropocene. Maybe instead of on a pedestal, we are supposed to put nature on an ordinary windowsill and place our bets on who eats who in this S/M relationship. Maybe nature doesn’t really care how much we try to appeal to her. And maybe acting less surprised would appease her a little bit so that she spares some of us in the end.

Written by Elias Wagner