27/09/2018 – 09/11/2018

Rachel Libeskind, War (&) EtiquetteRachel Libeskind, War (&) Etiquette

27/09/2018 – 09/11/2018

Rachel Libeskind, War (&) Etiquette

Exhibition ViewExhibition View

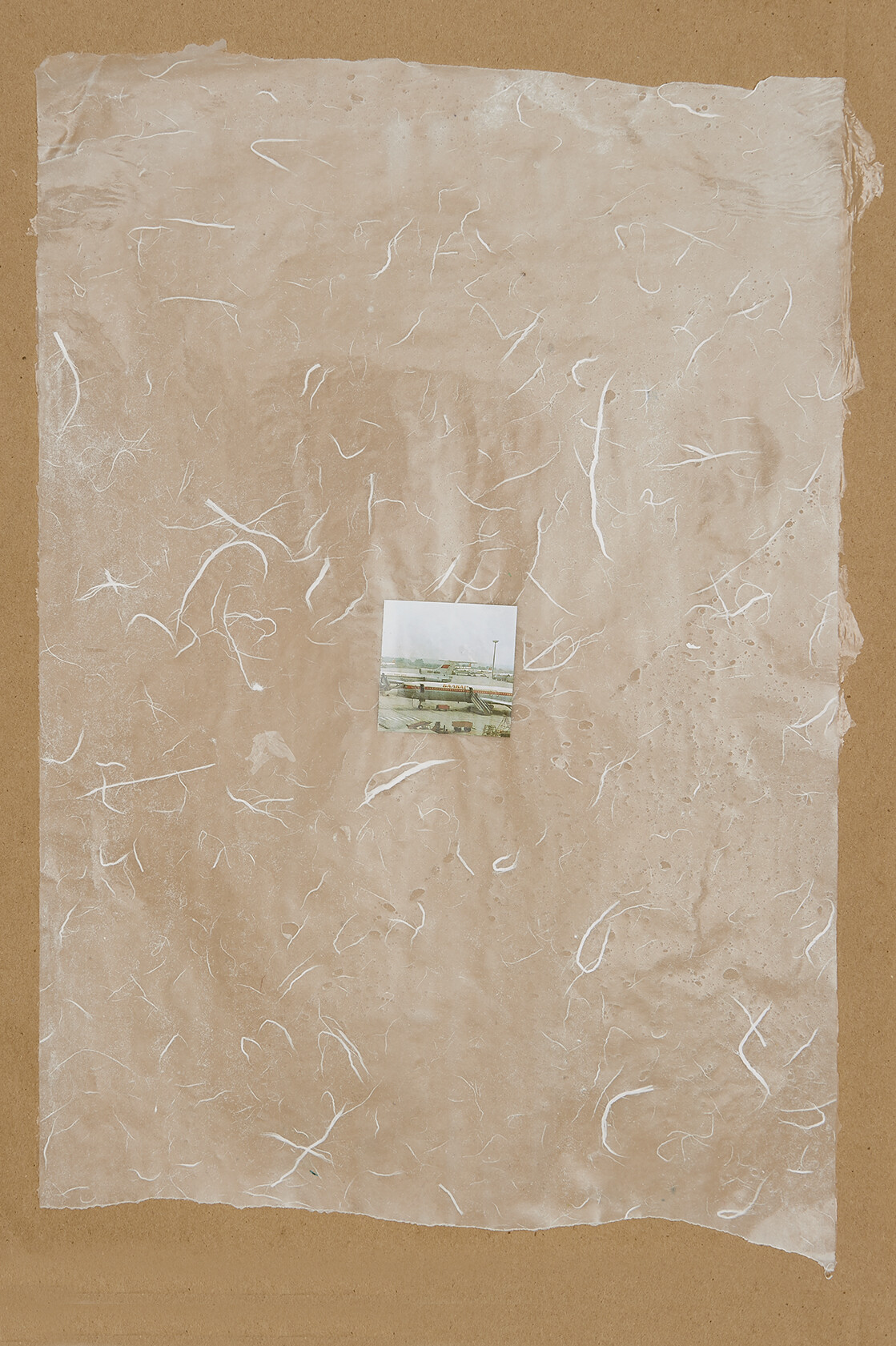

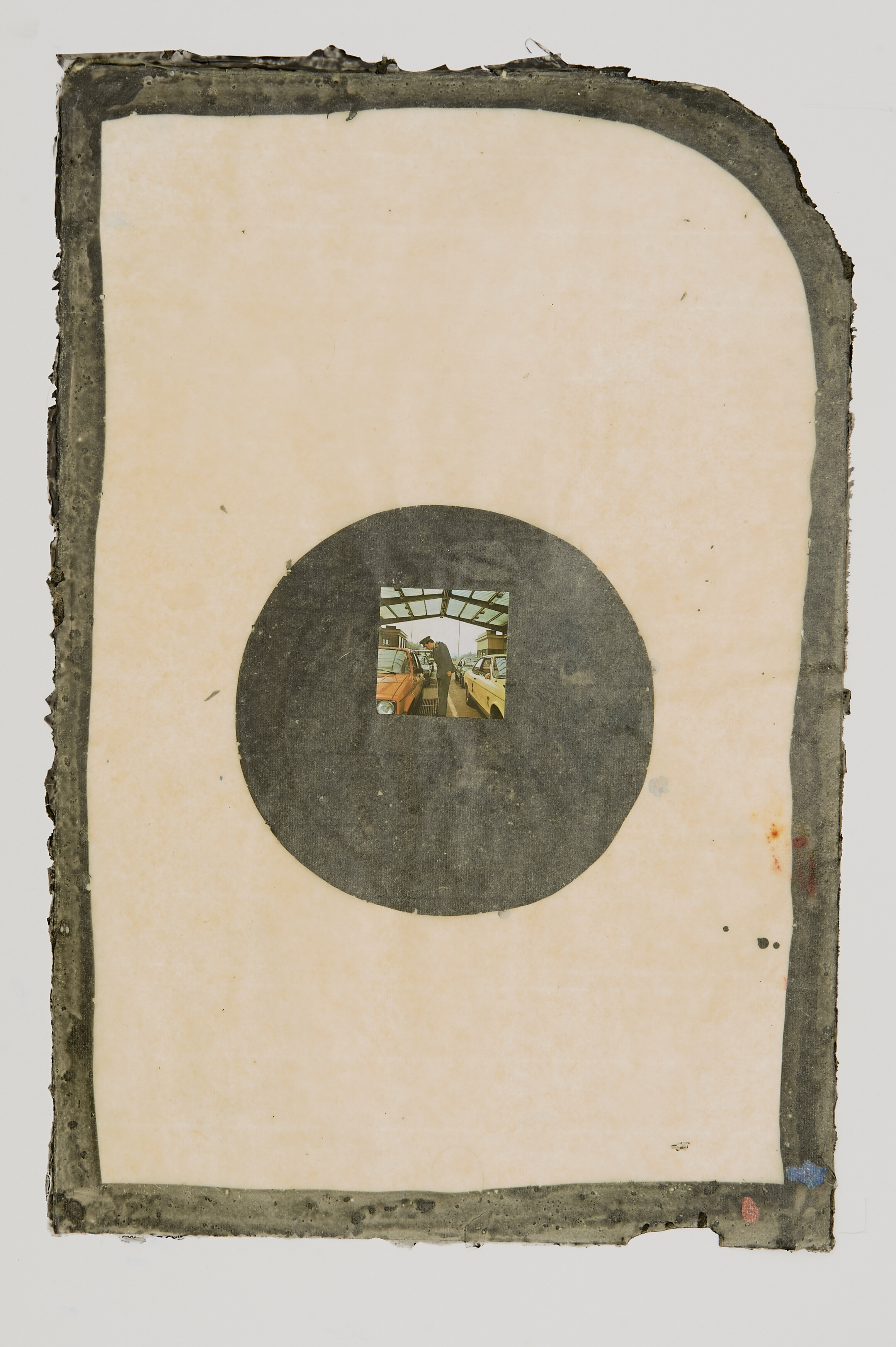

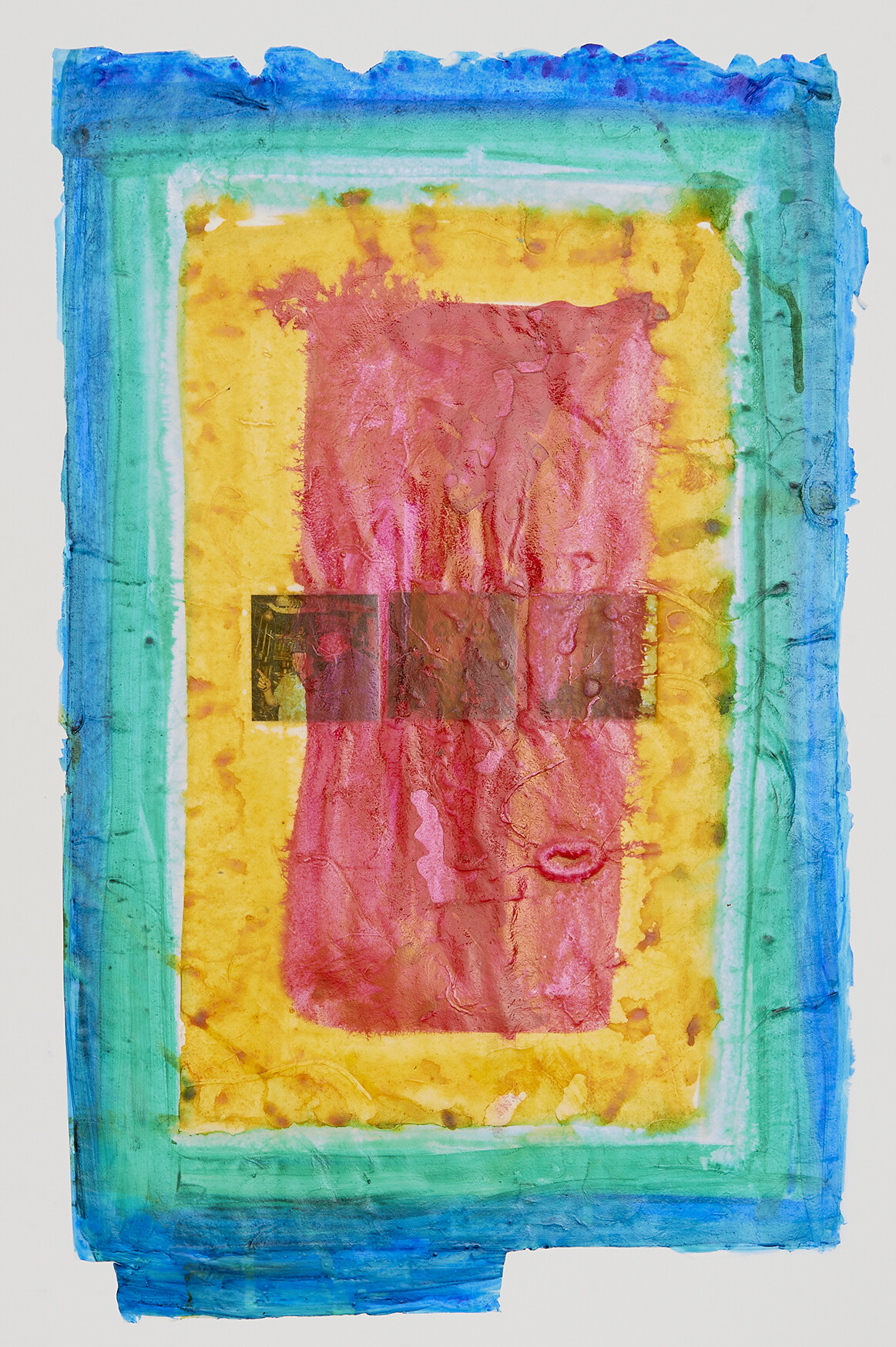

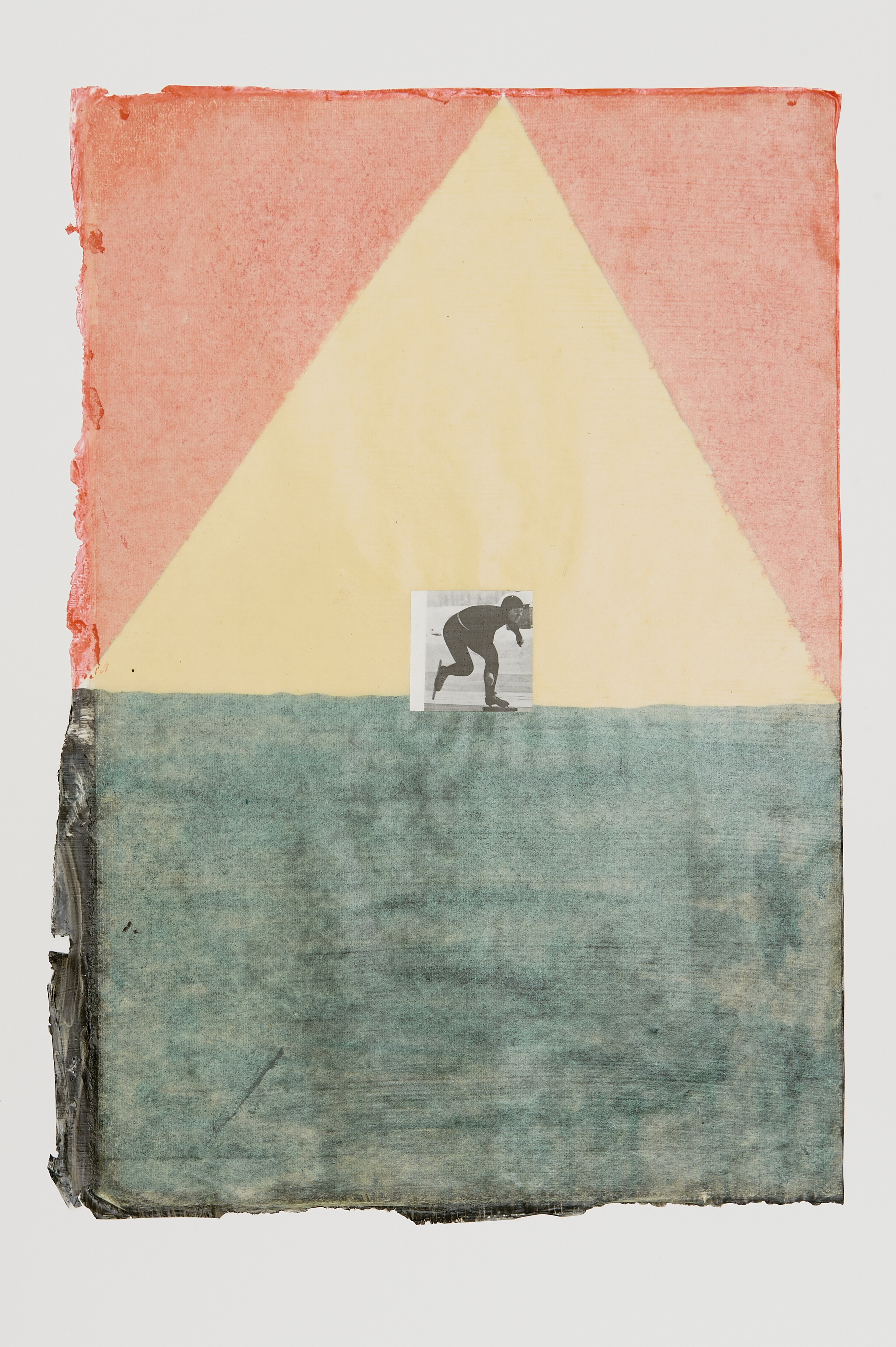

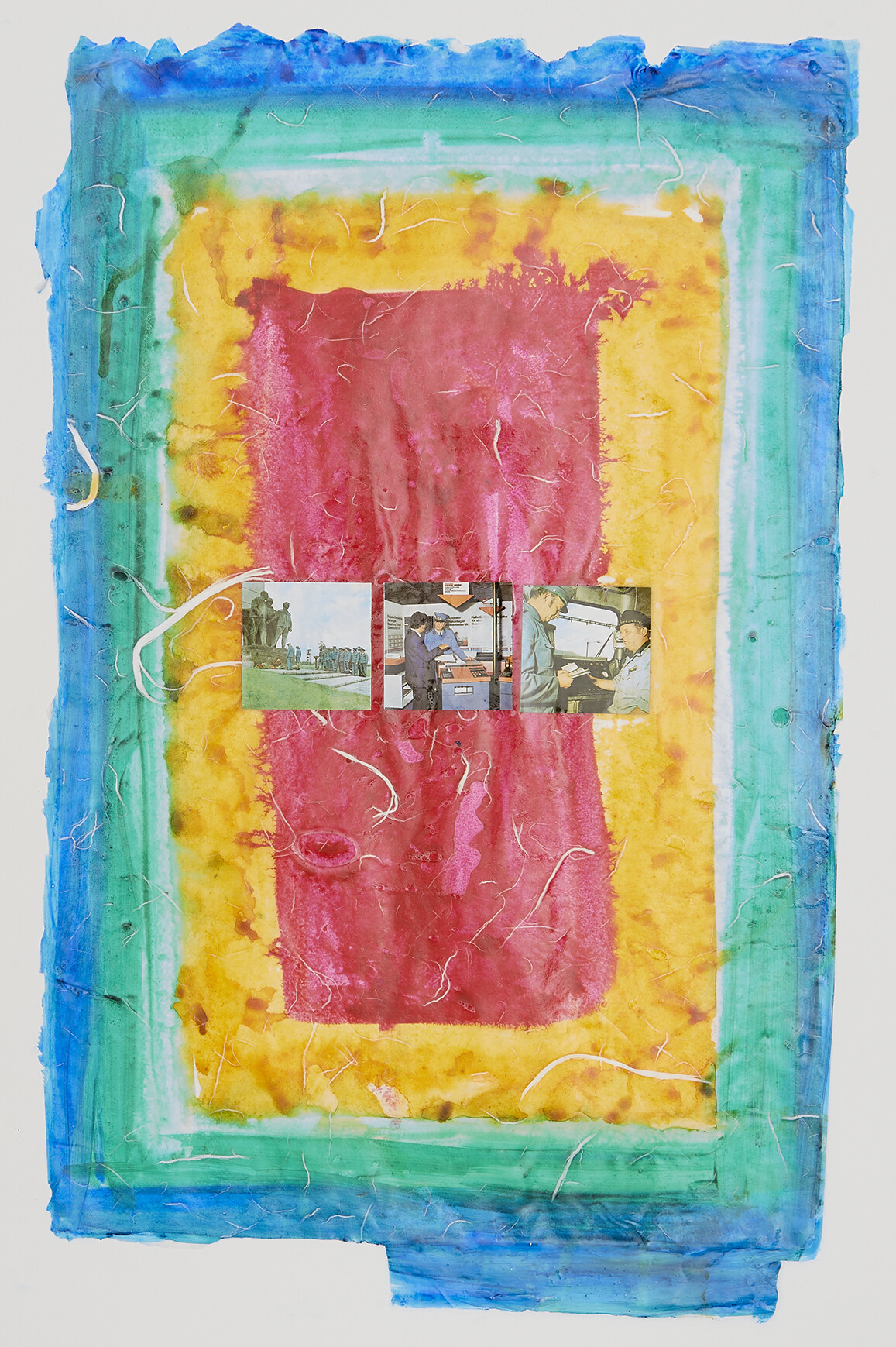

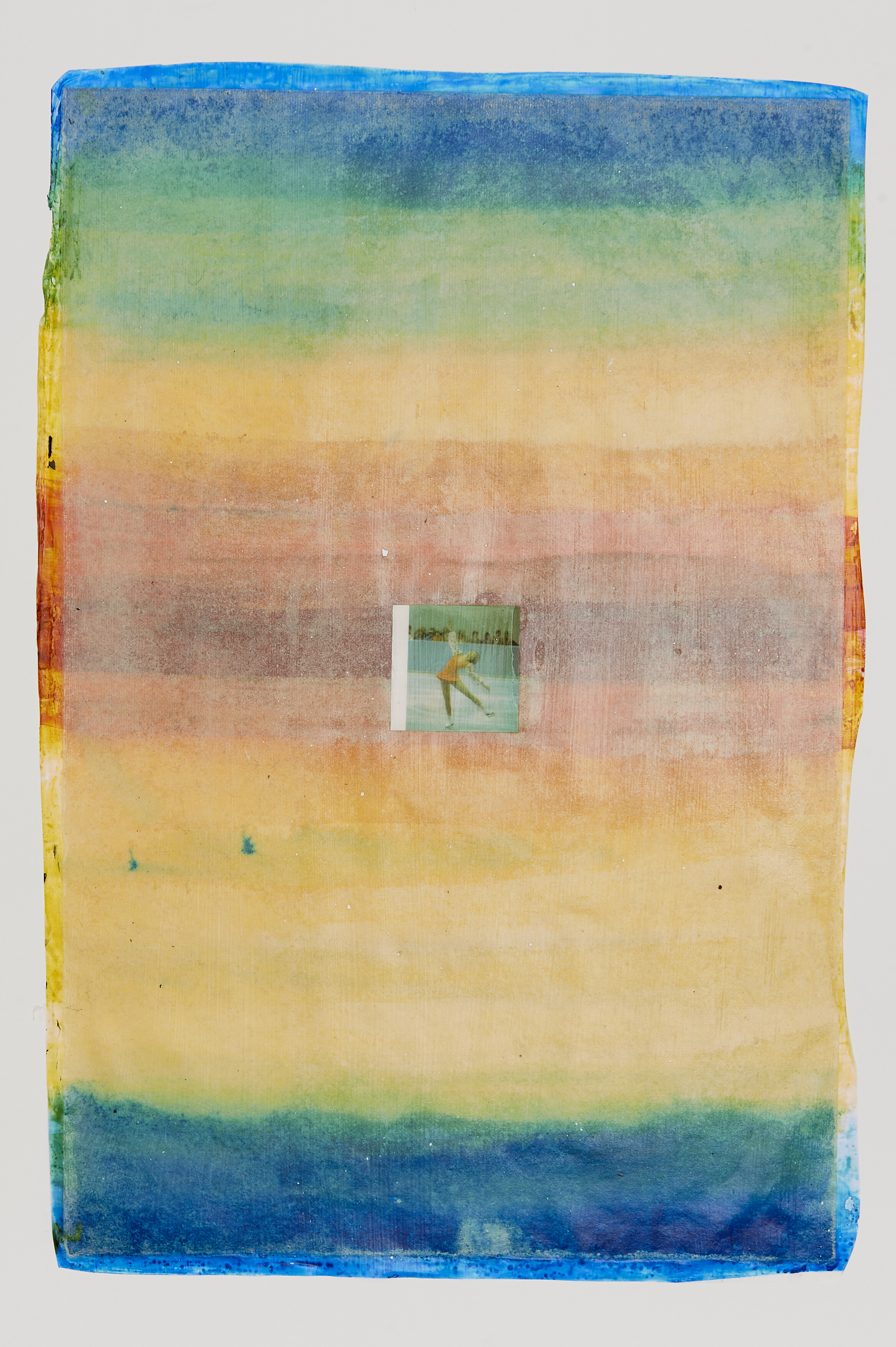

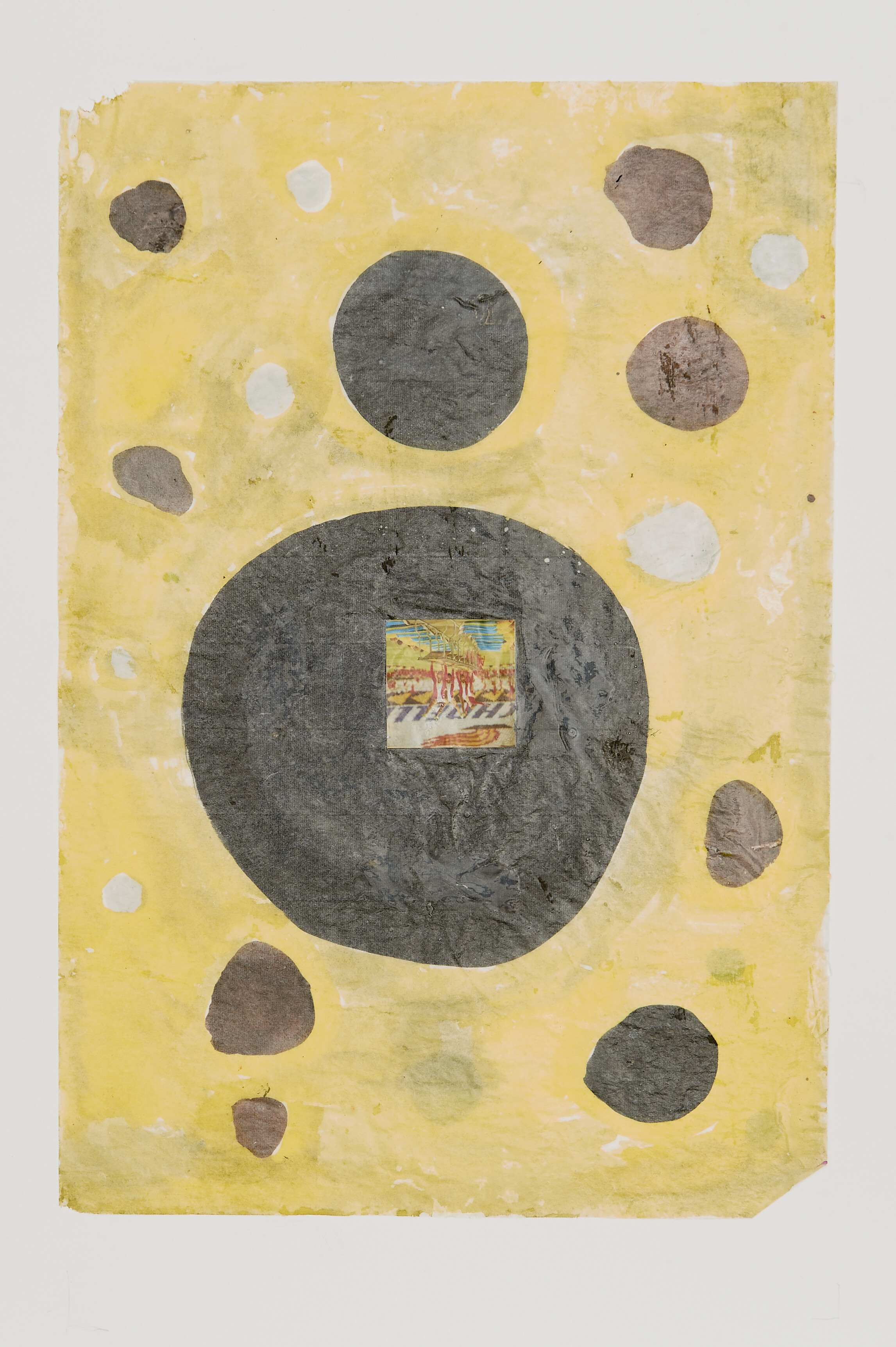

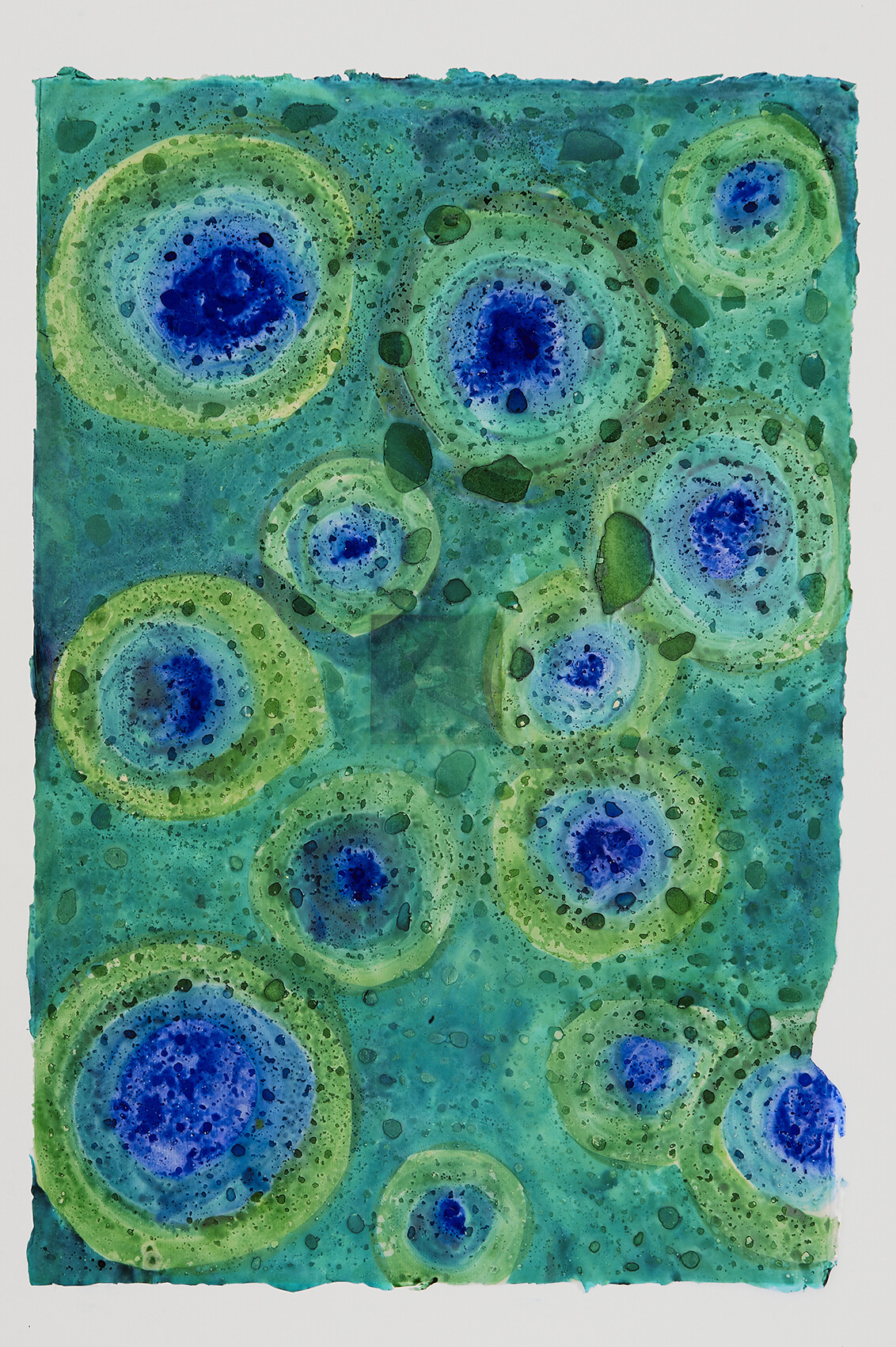

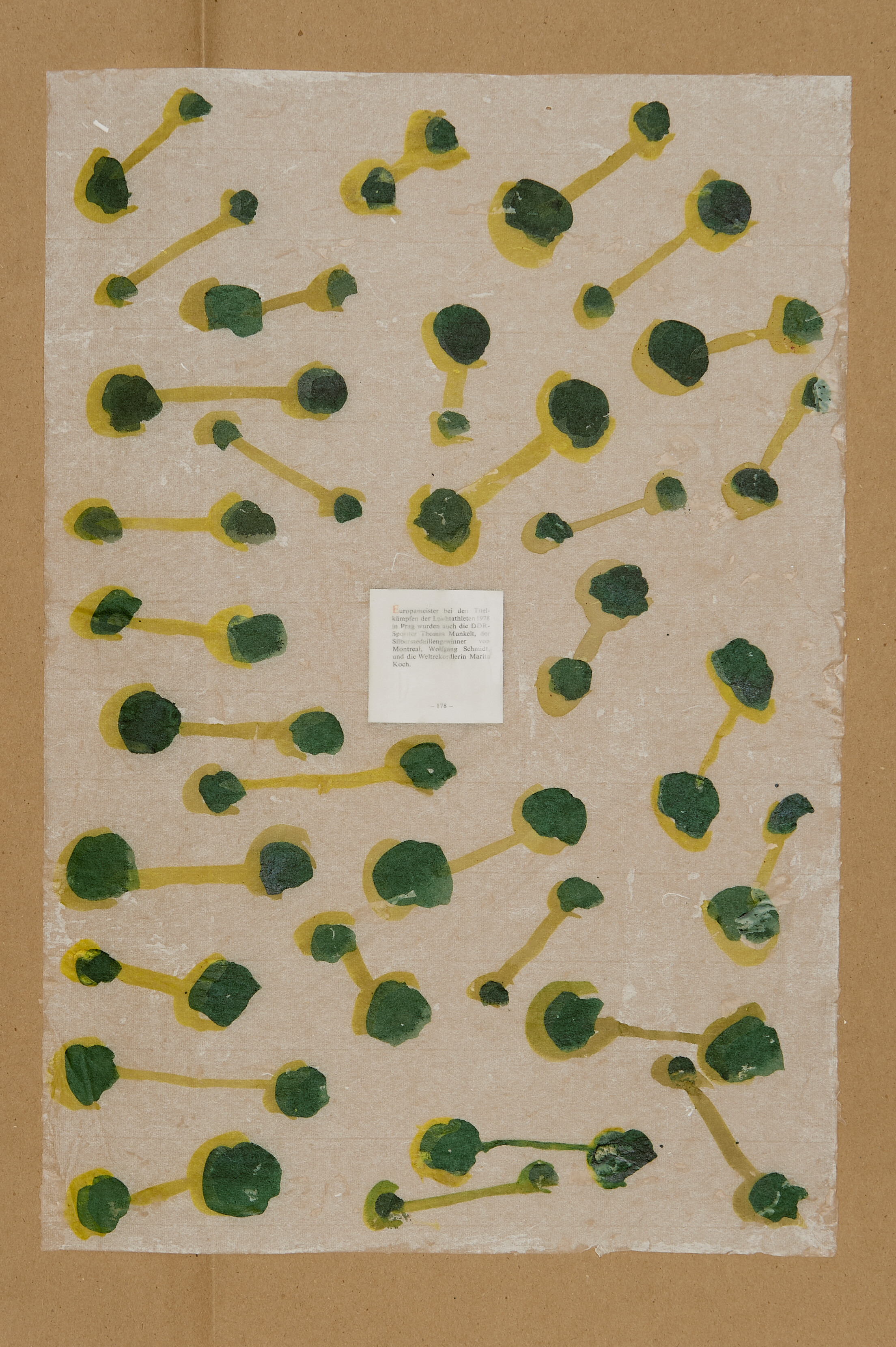

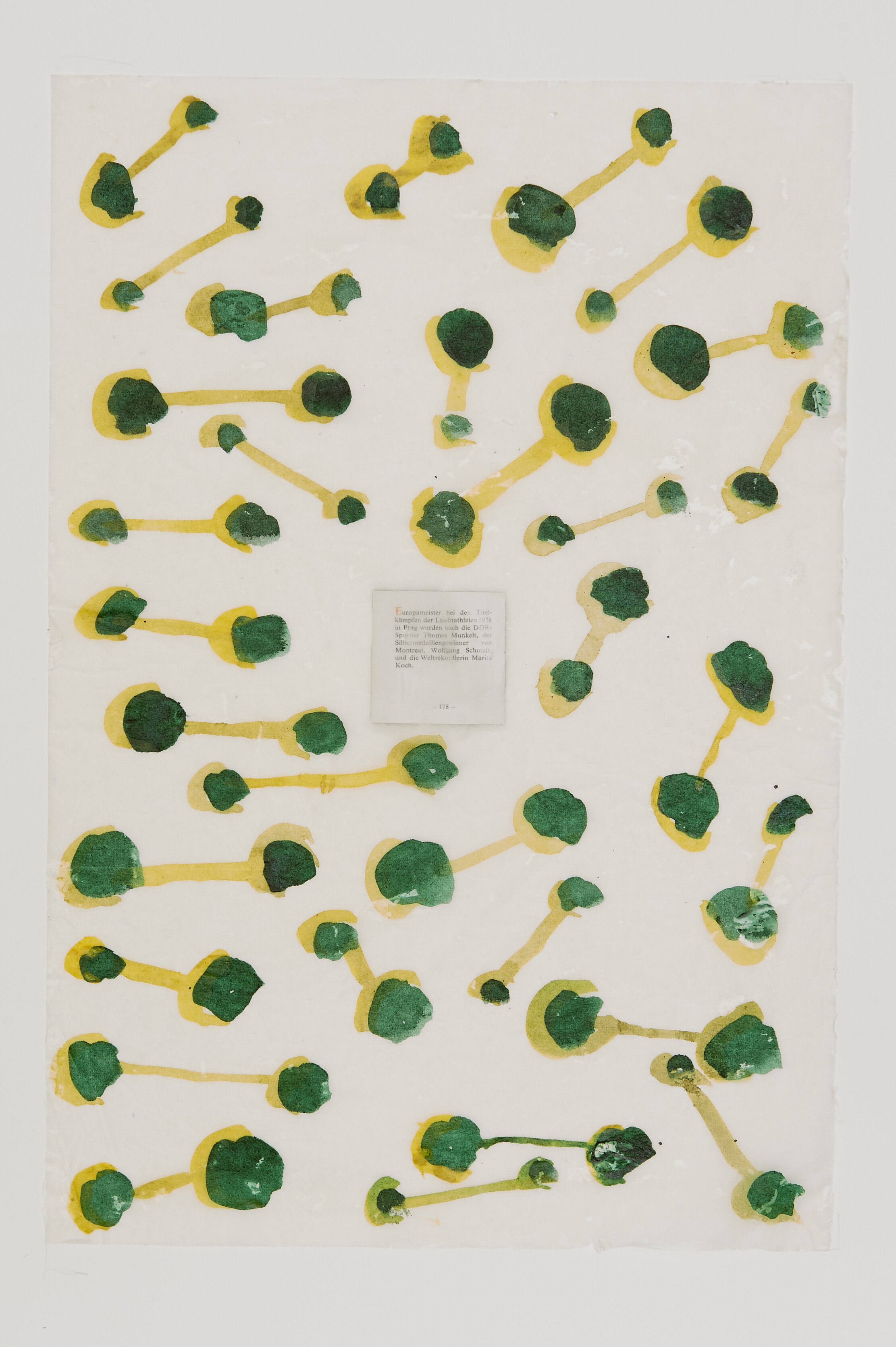

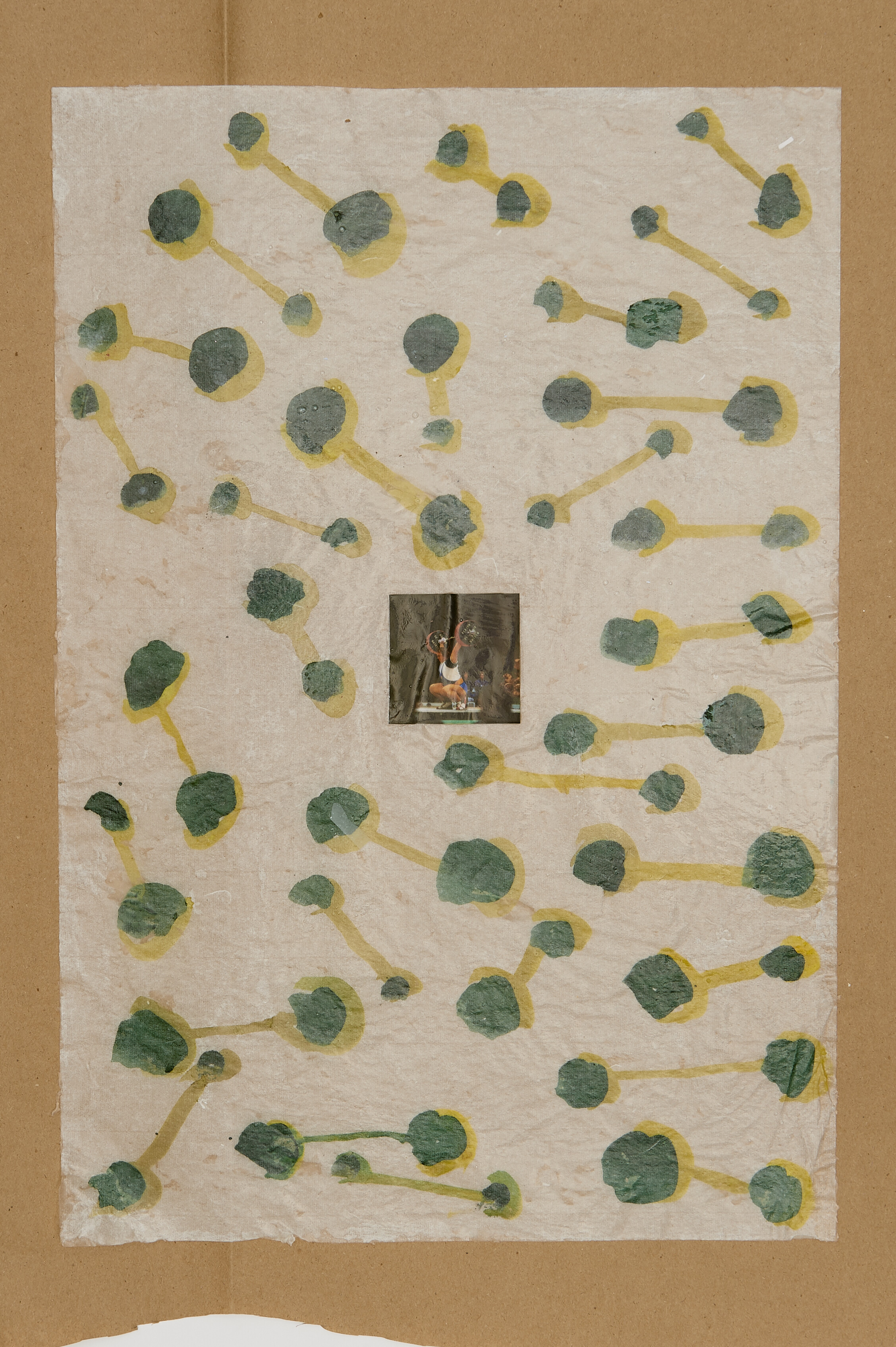

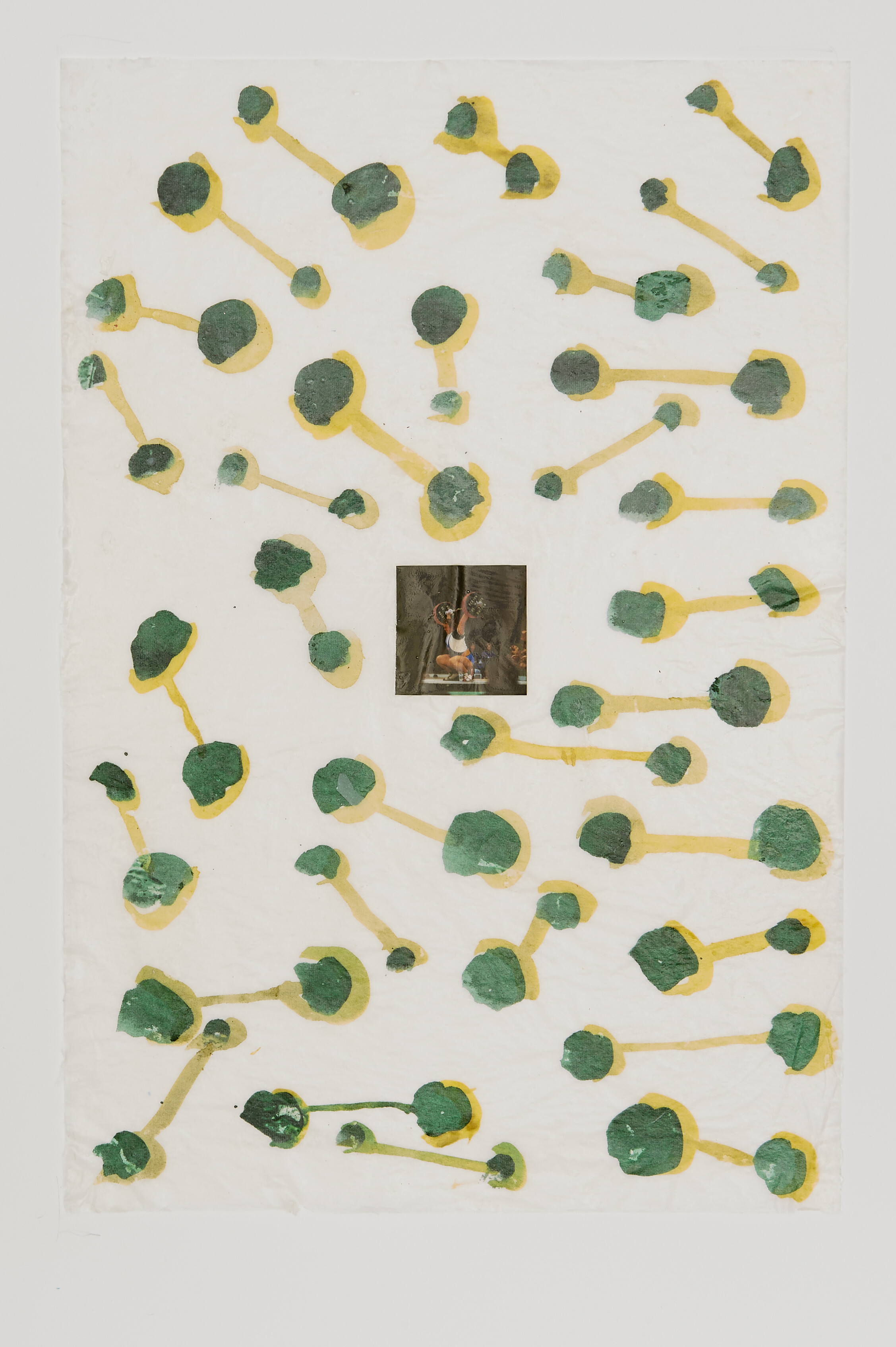

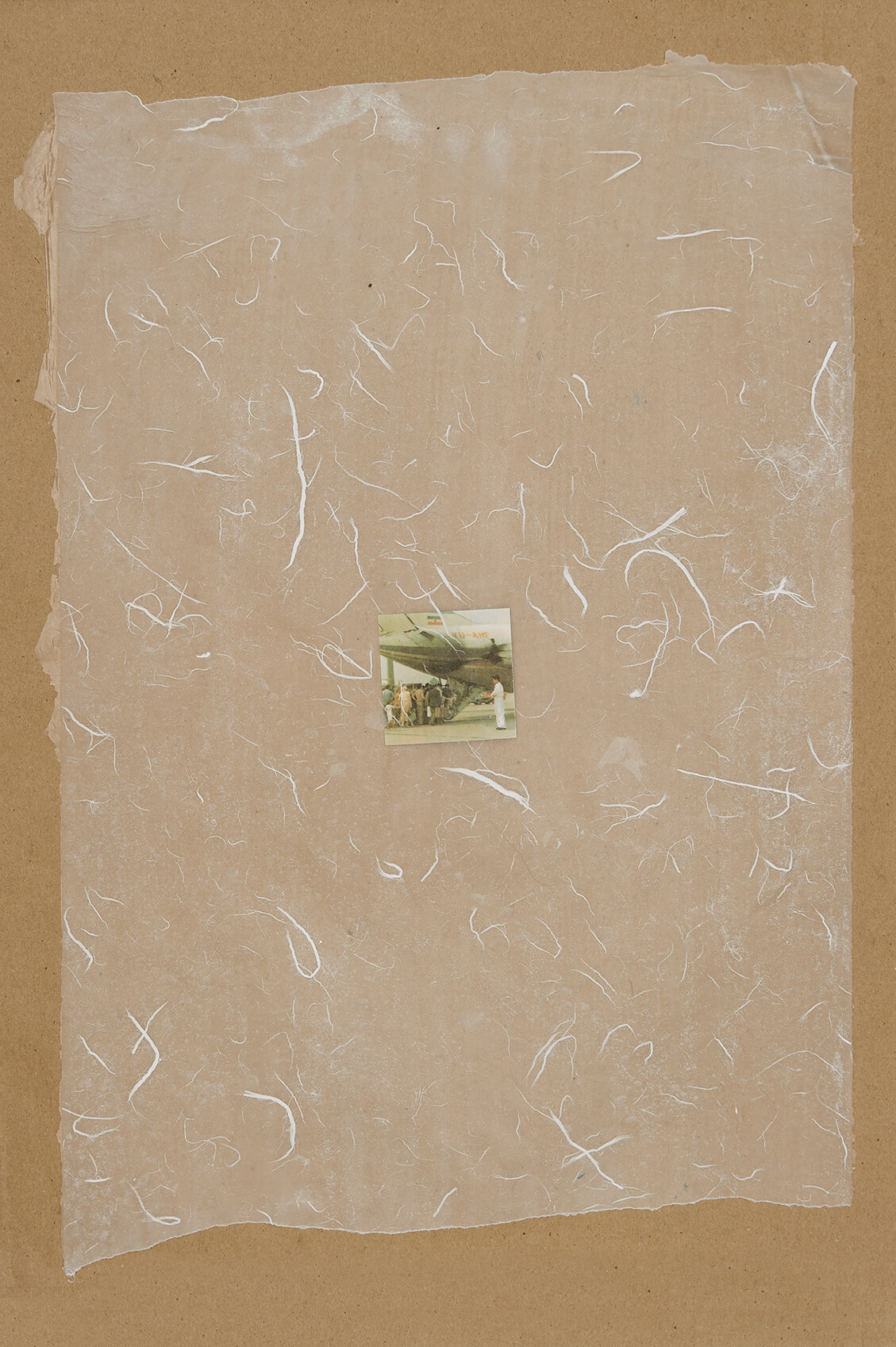

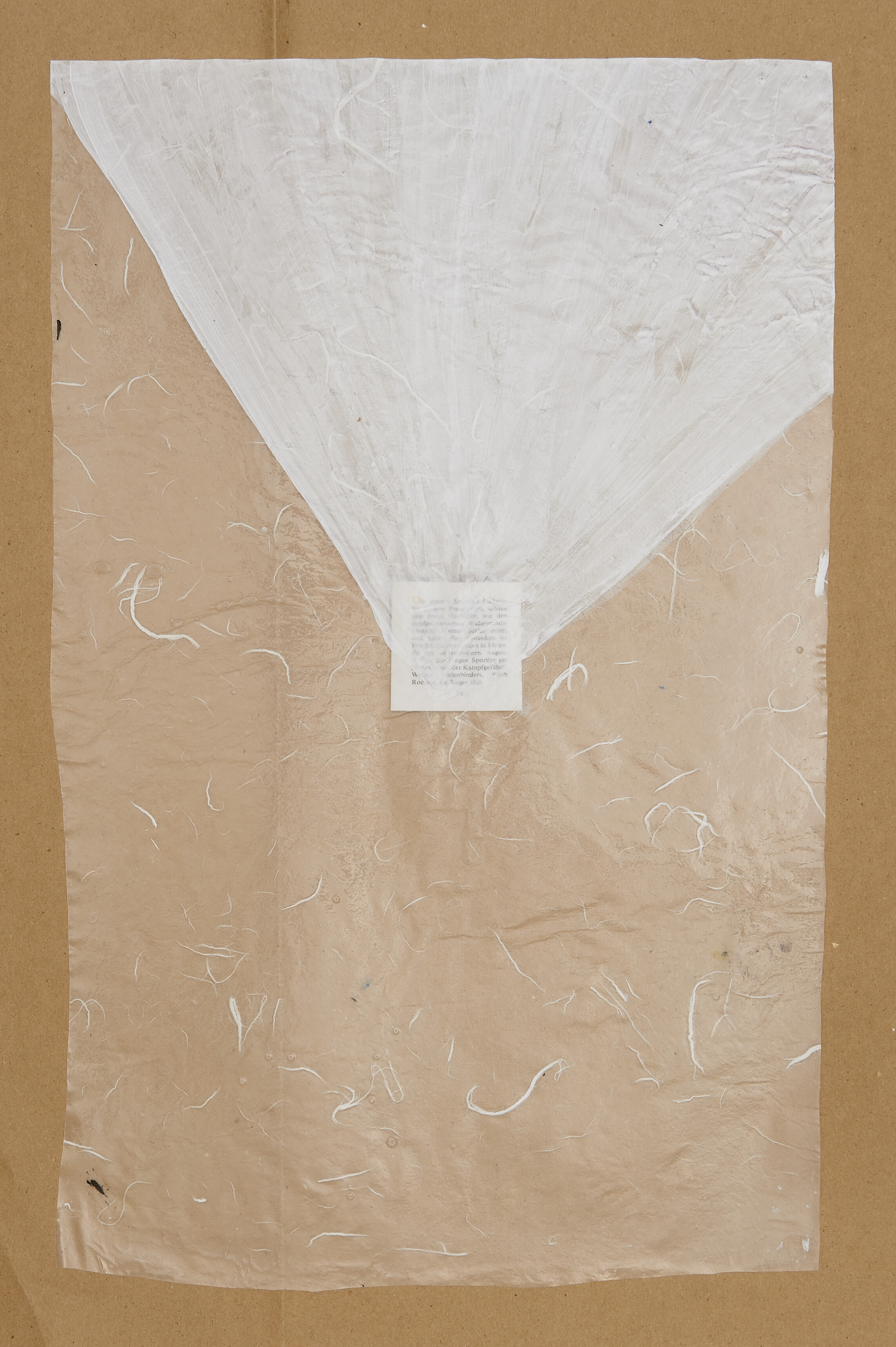

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

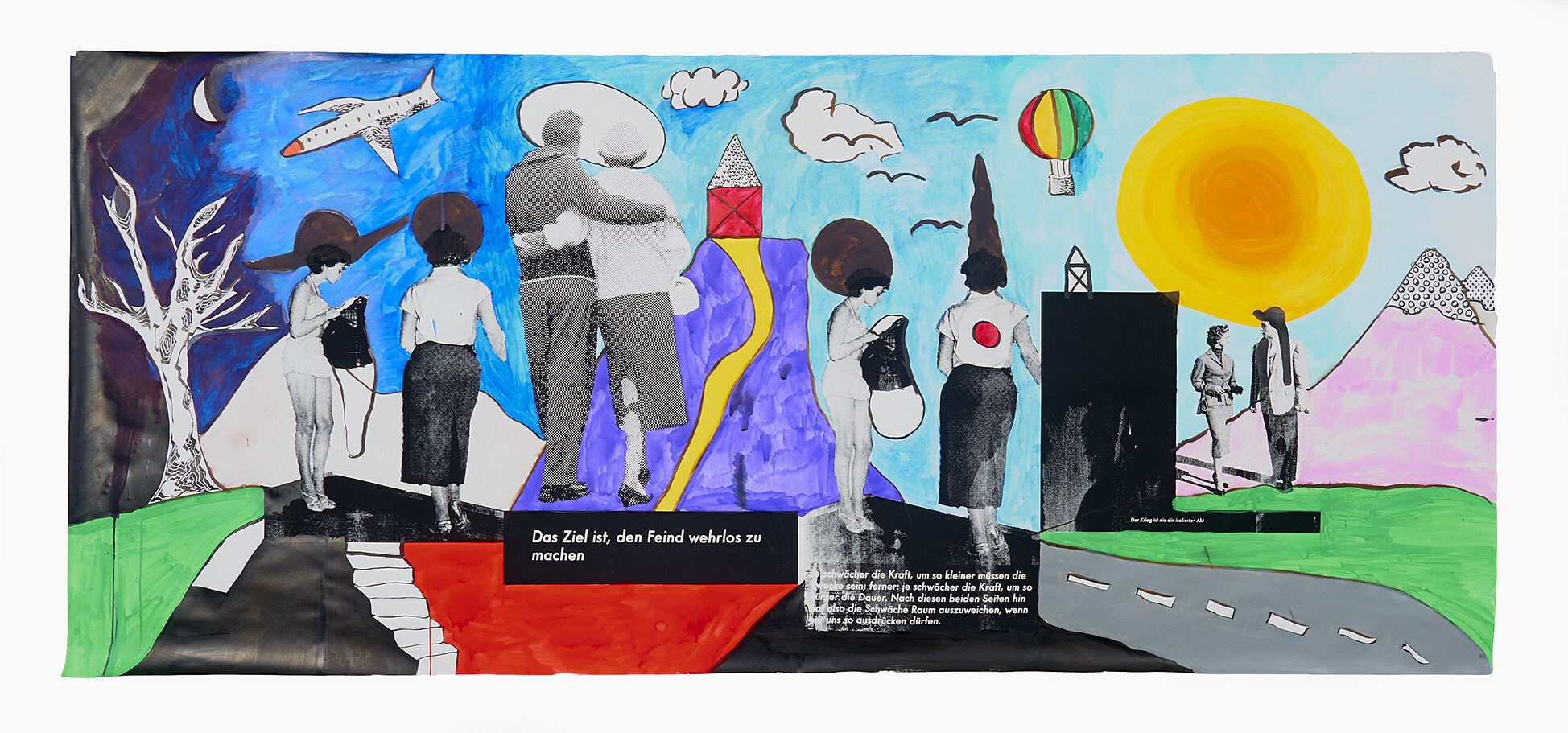

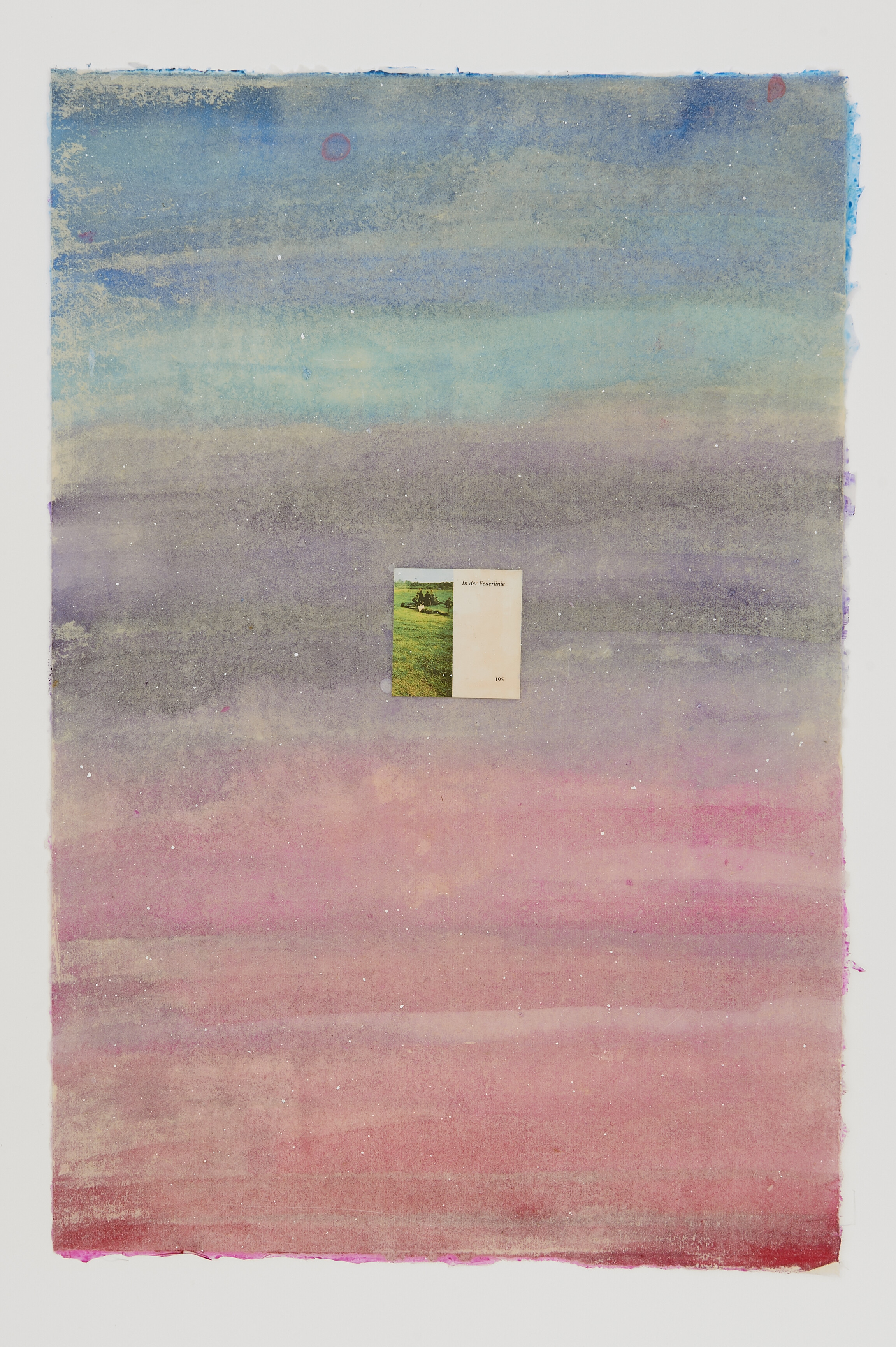

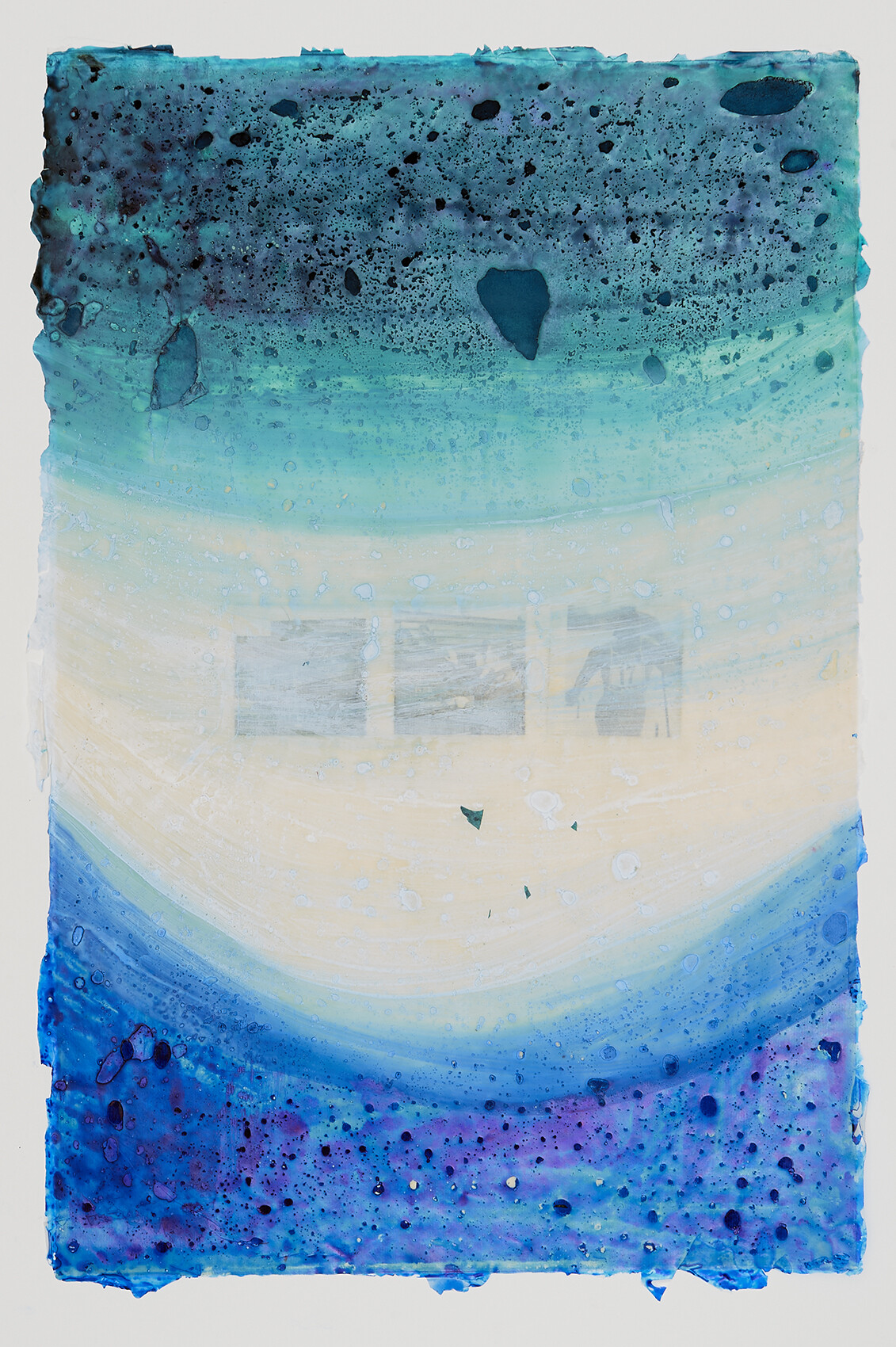

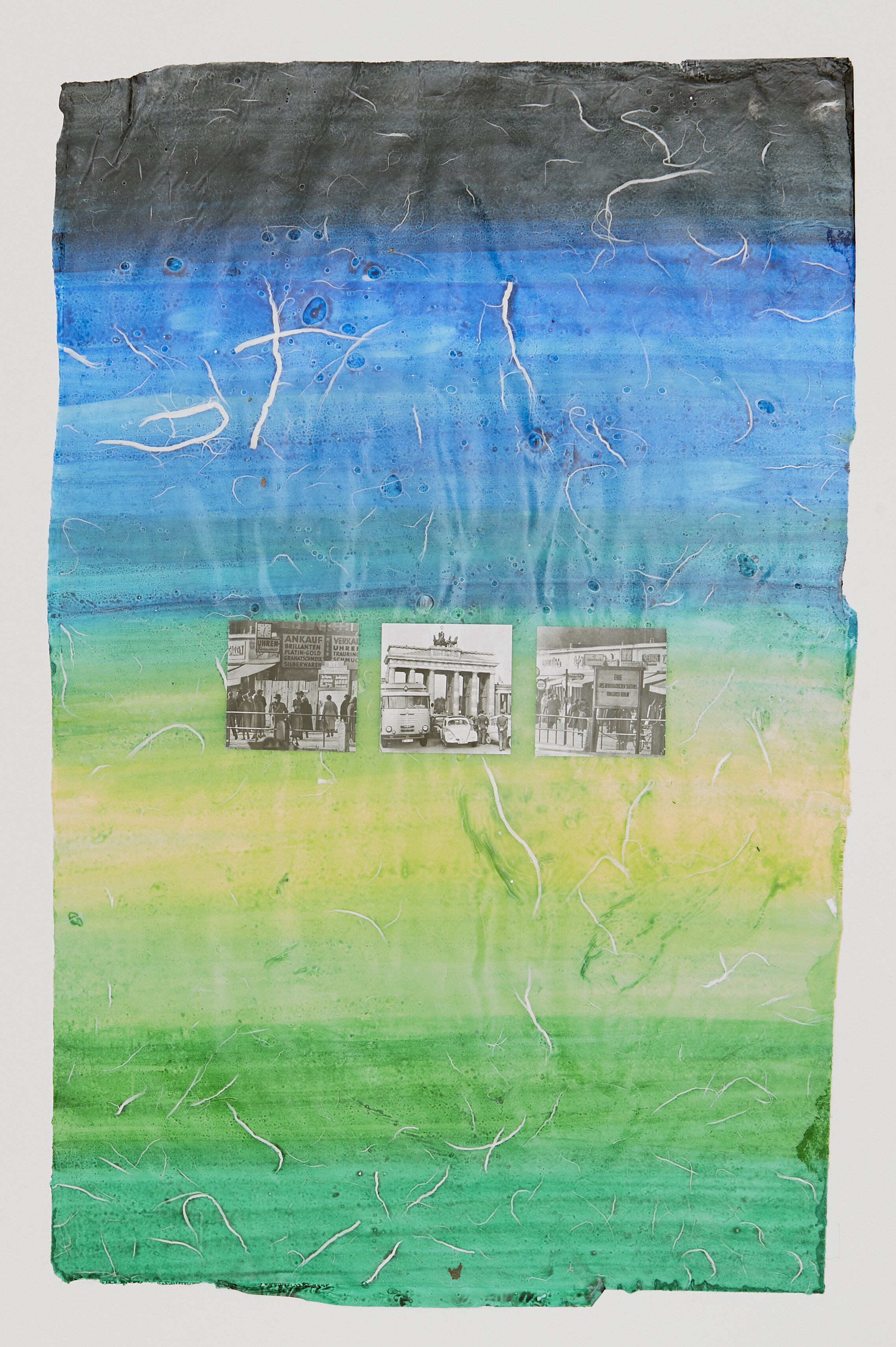

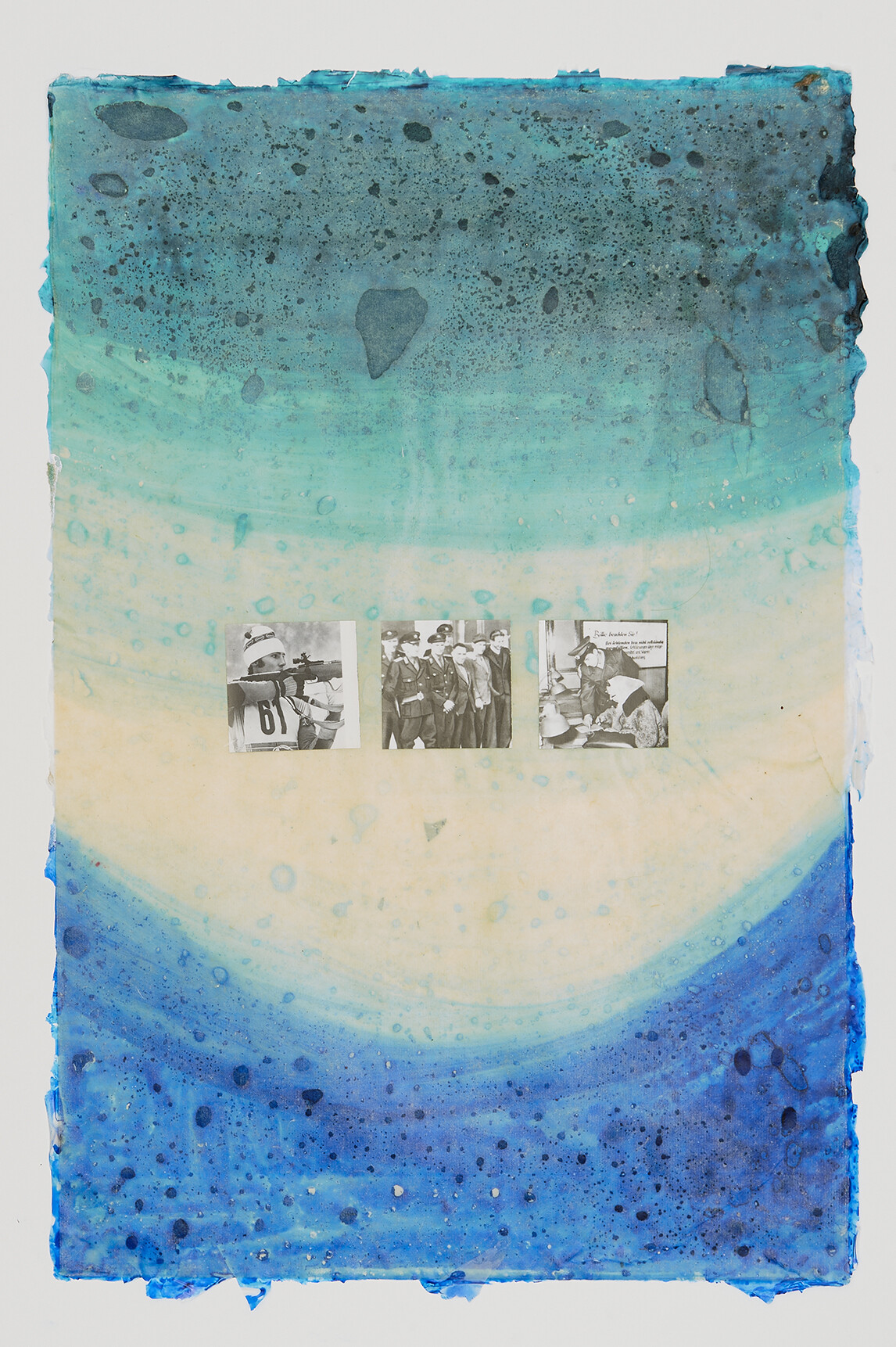

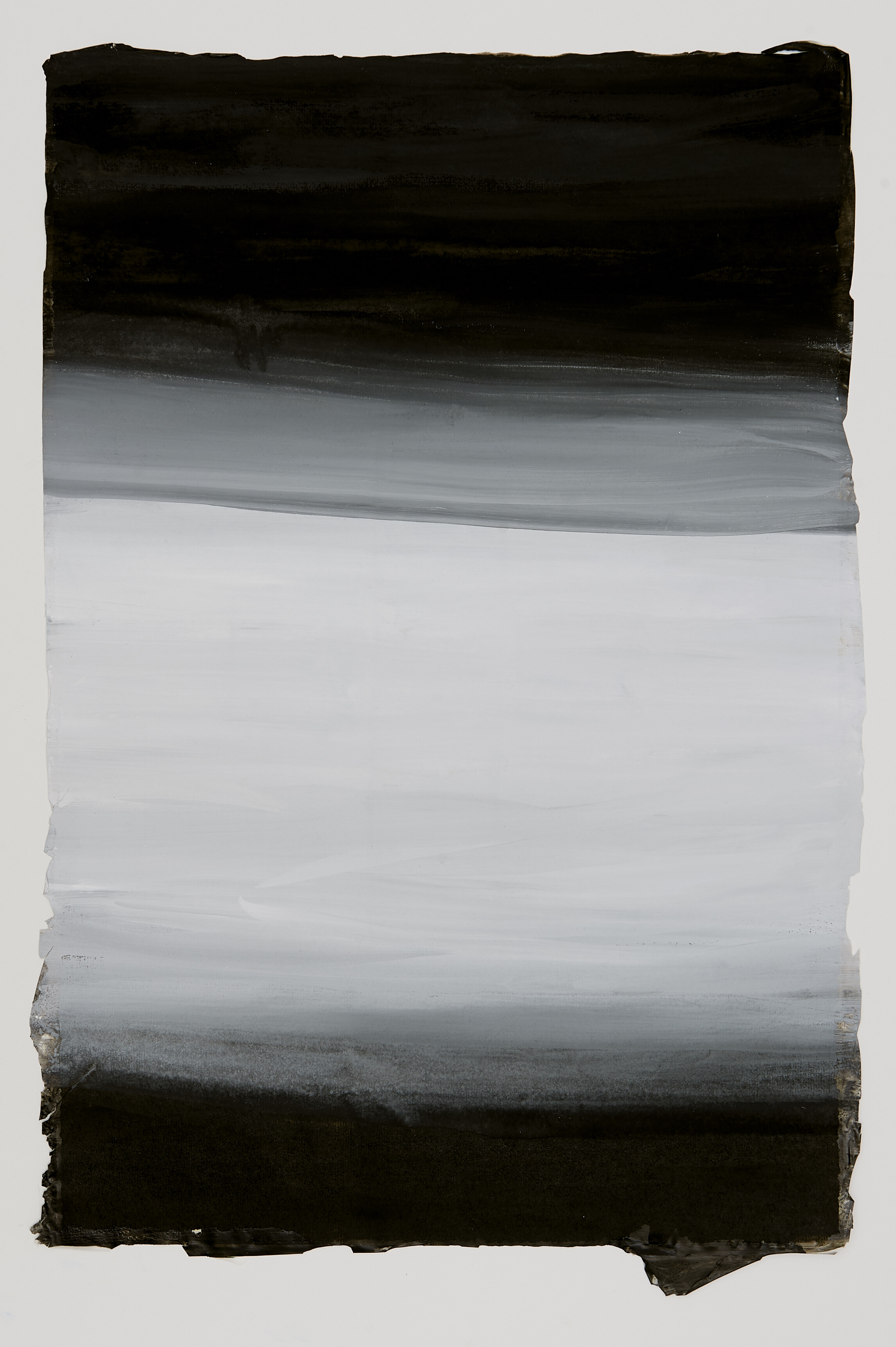

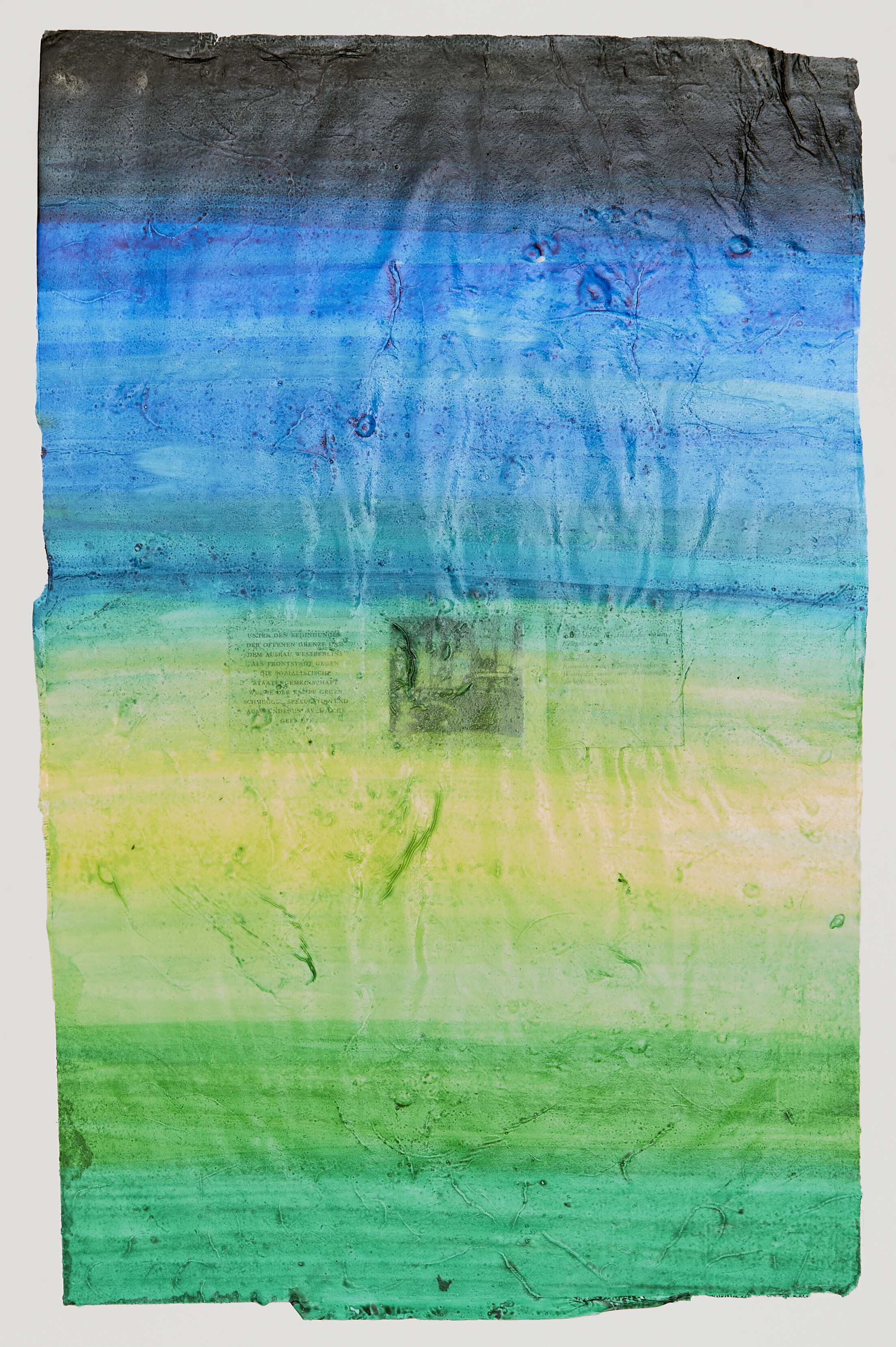

Landscape of Yesterday and Tomorrow, Watercolor concentrate, India ink, acrylic paint and silkscreen on mixed media paper, 106 x 228 cm, 2018Landscape of Yesterday and Tomorrow, Watercolor concentrate, India ink, acrylic paint and silkscreen on mixed media paper, 106 x 228 cm, 2018

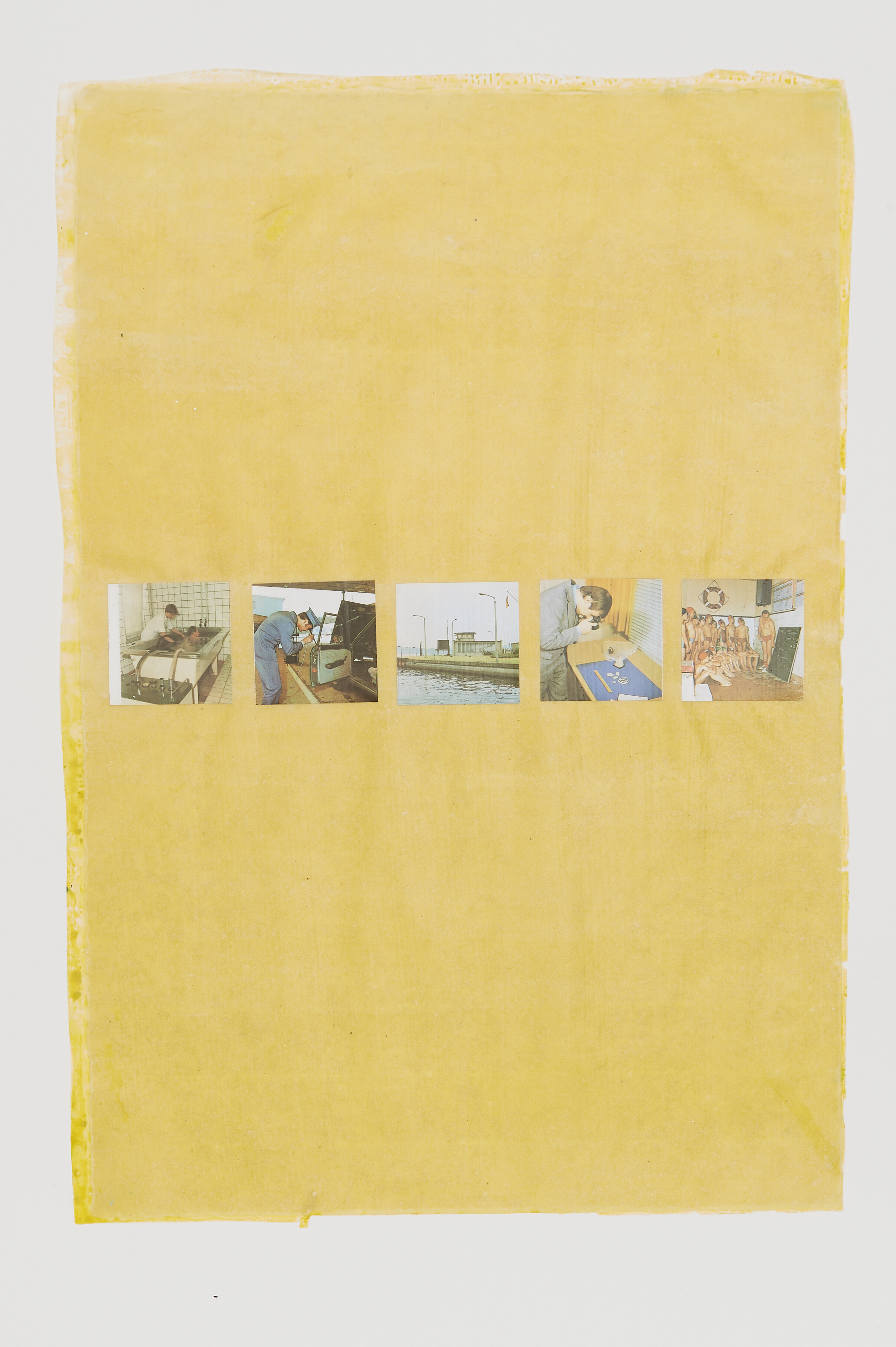

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

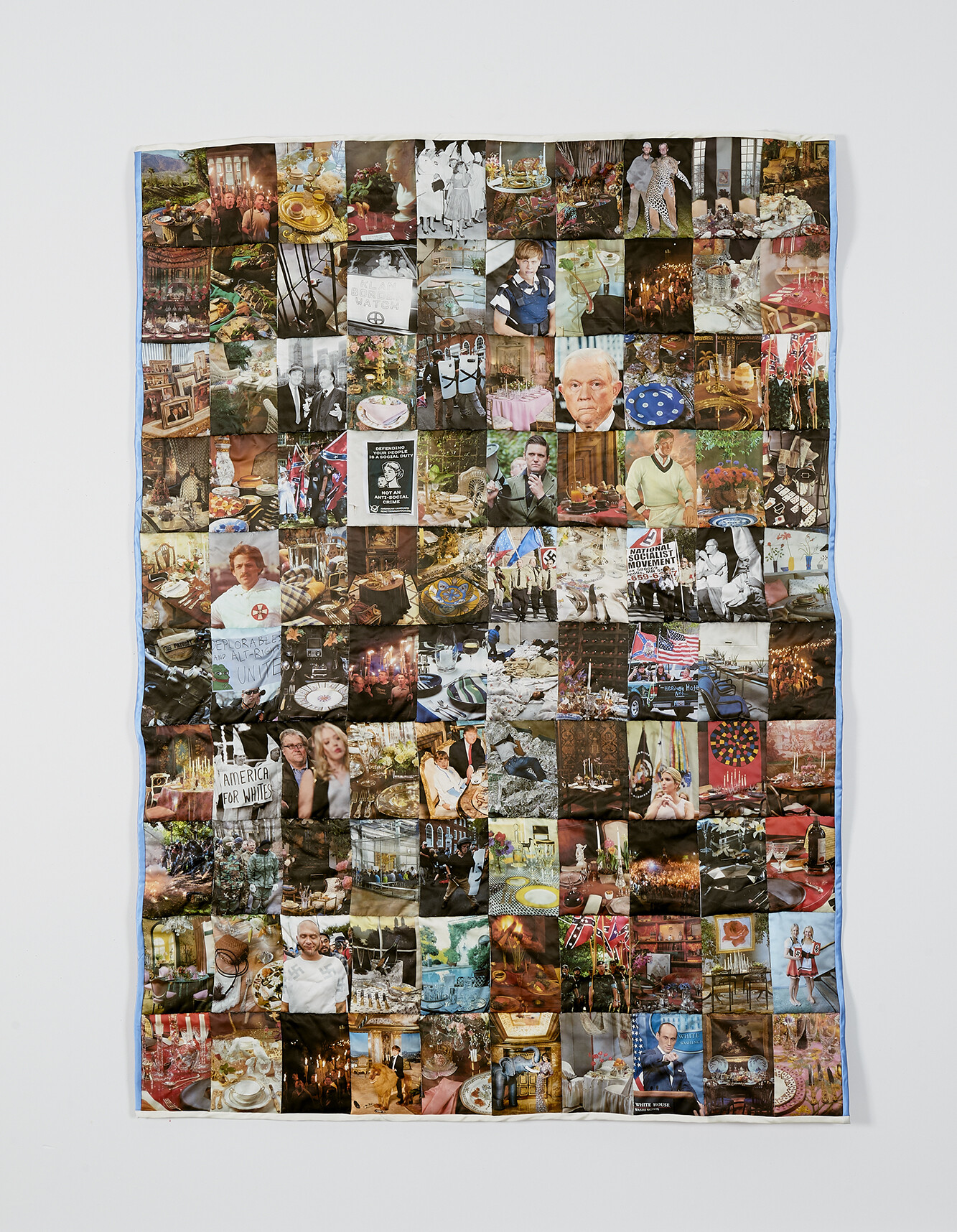

Security Blanket, Inkjet on silk, wool batting, 152.4 x 203.2 cm, 2018Security Blanket, Inkjet on silk, wool batting, 152.4 x 203.2 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

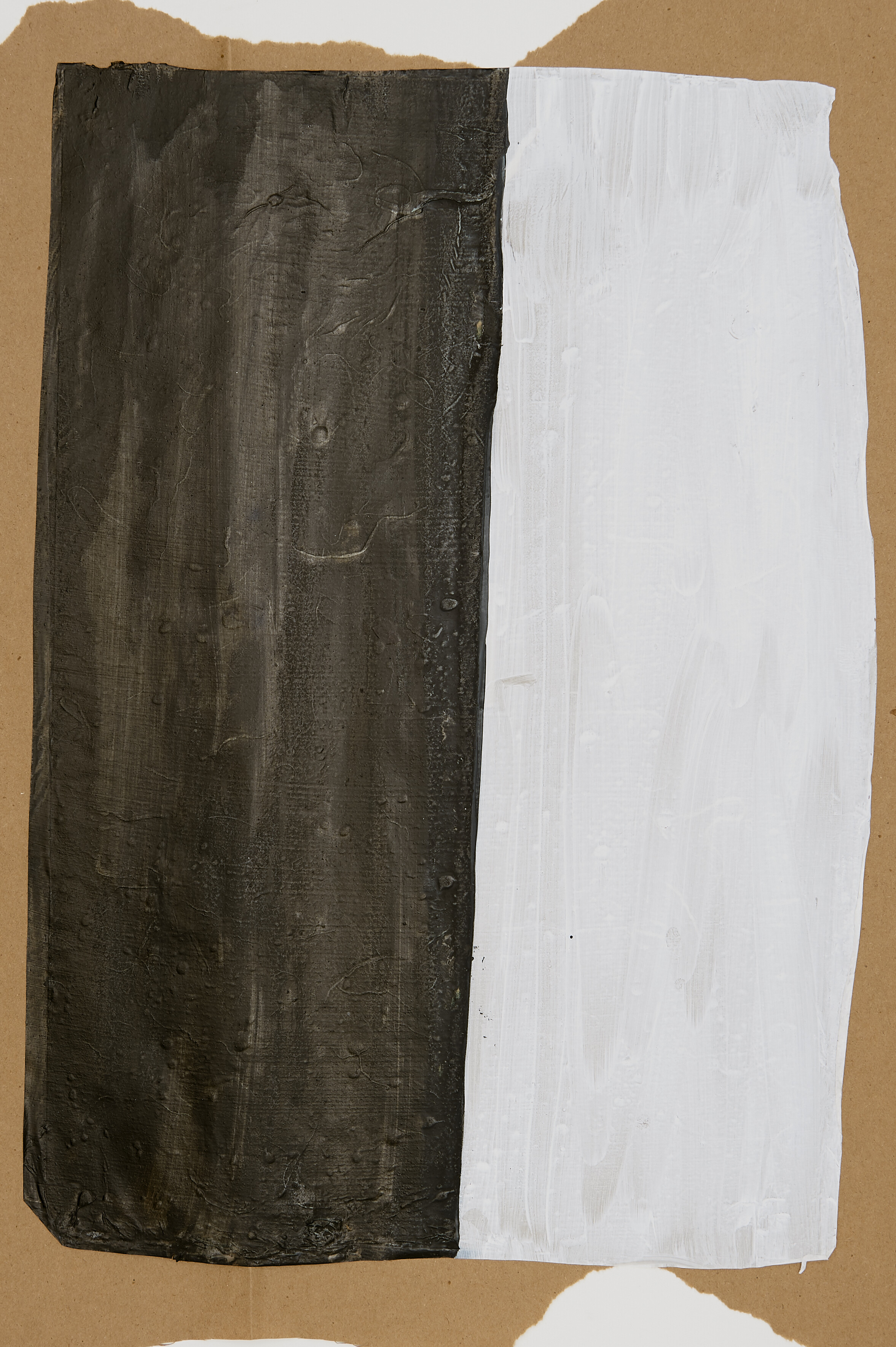

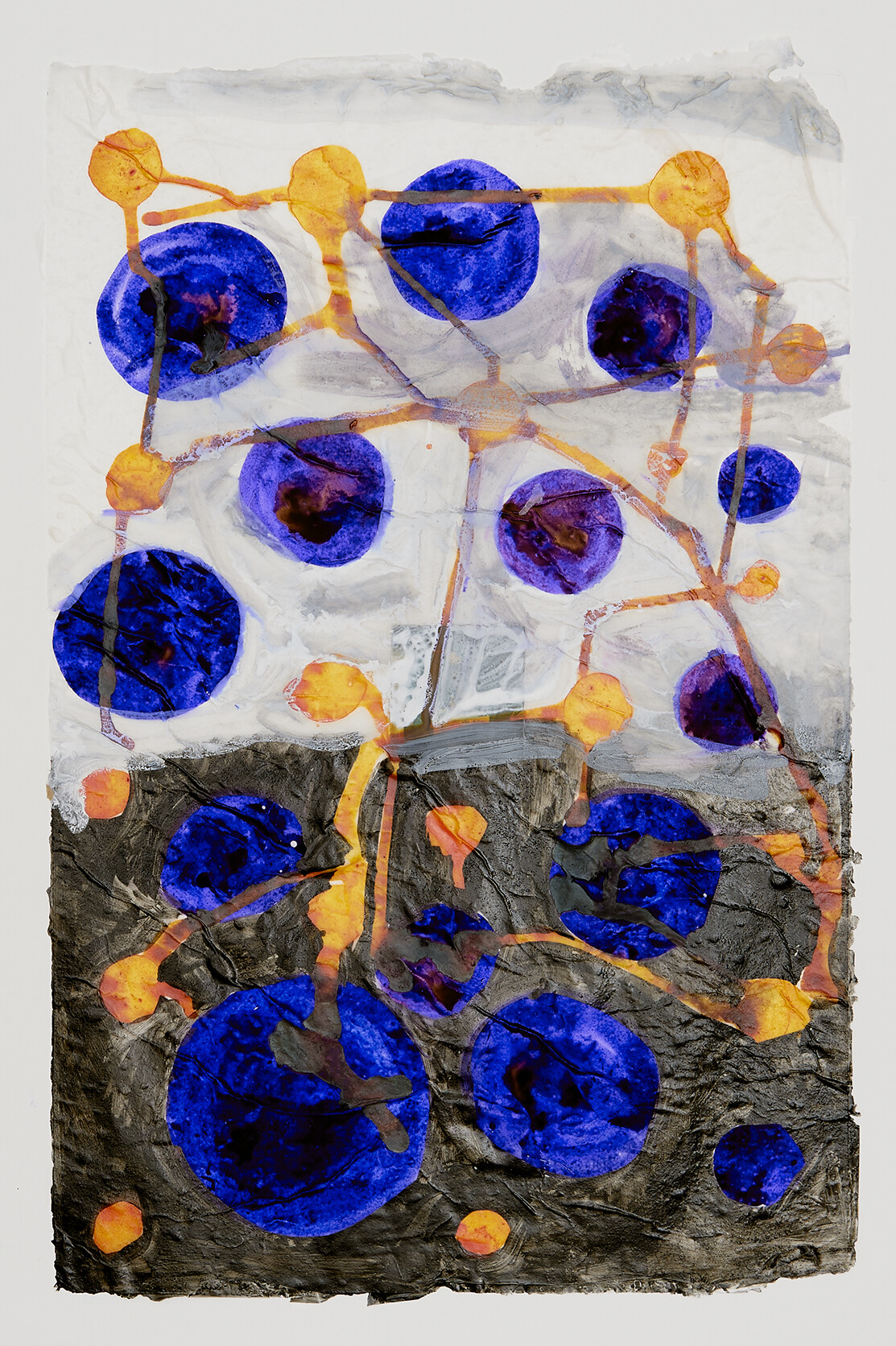

Dusk Scene, Silkscreen, ink, acrylic paint on Strathmore paper, 106 x 108 cm, 2018Dusk Scene, Silkscreen, ink, acrylic paint on Strathmore paper, 106 x 108 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Exhibition ViewExhibition View

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Exhibition ViewExhibition View

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

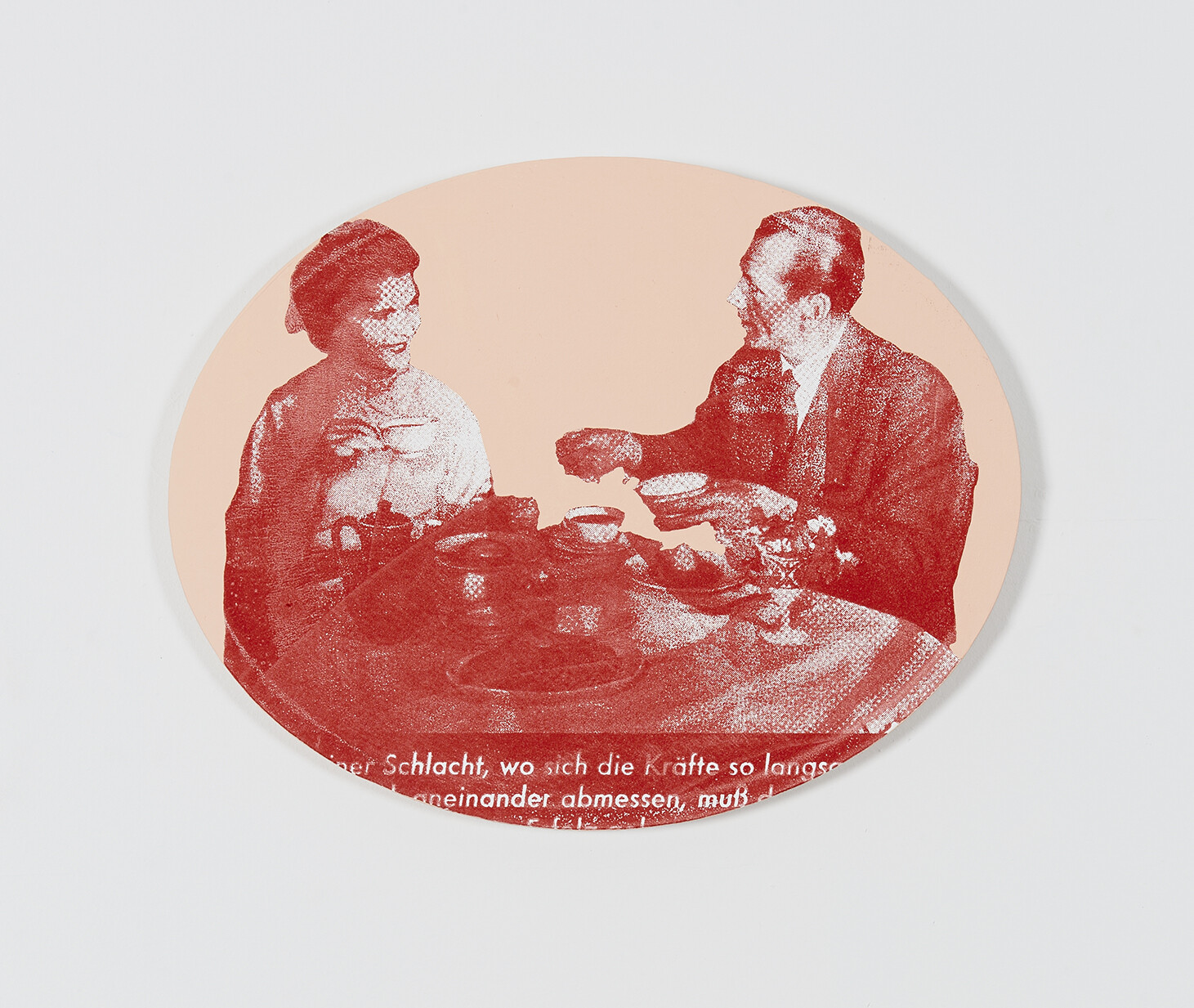

Dinner Rules 1, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 40 x 50 cm, 2018Dinner Rules 1, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 40 x 50 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Dinner Rules 3, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 400 x 50 cm, 2018Dinner Rules 3, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 400 x 50 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Exhibition ViewExhibition View

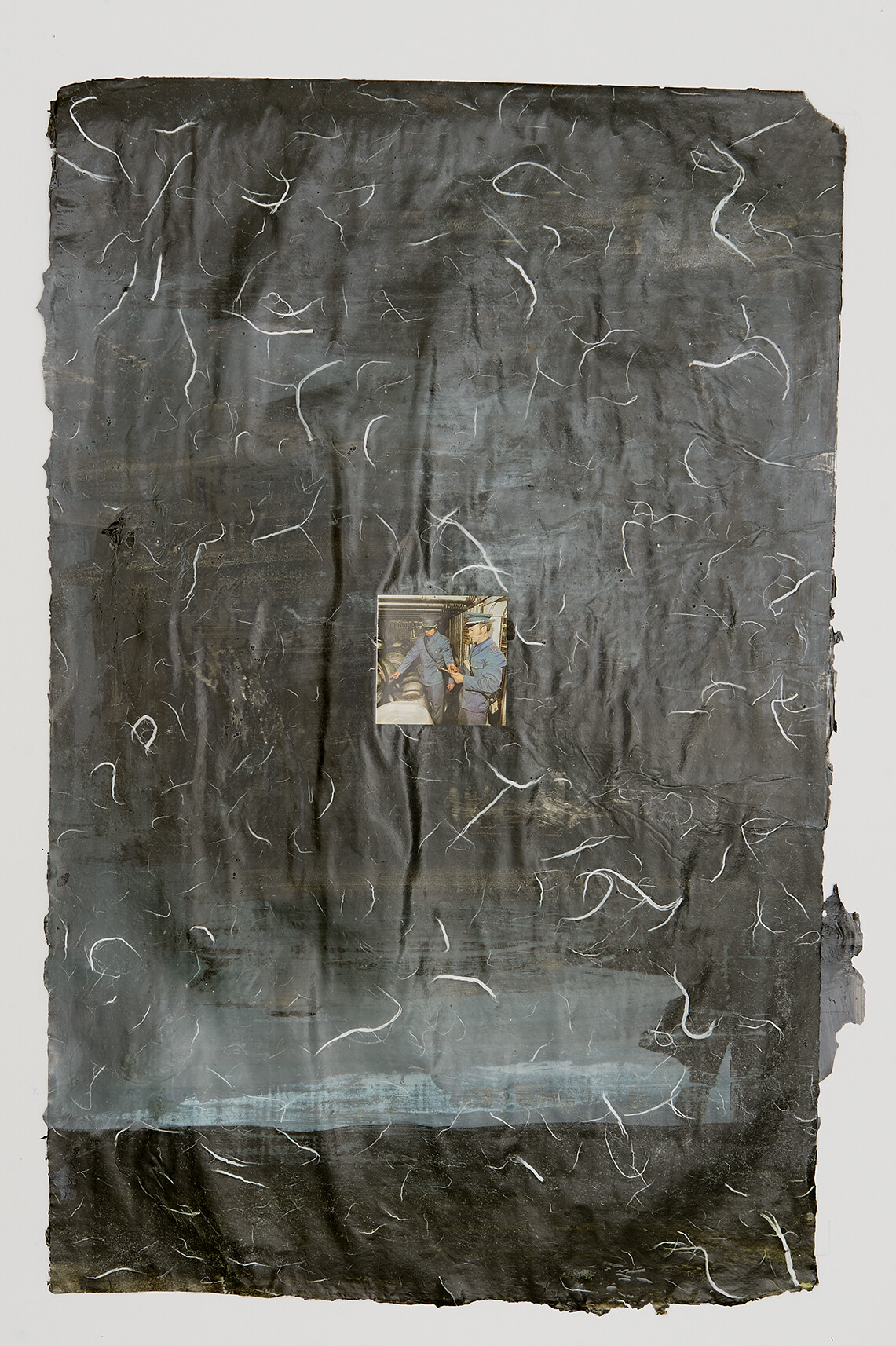

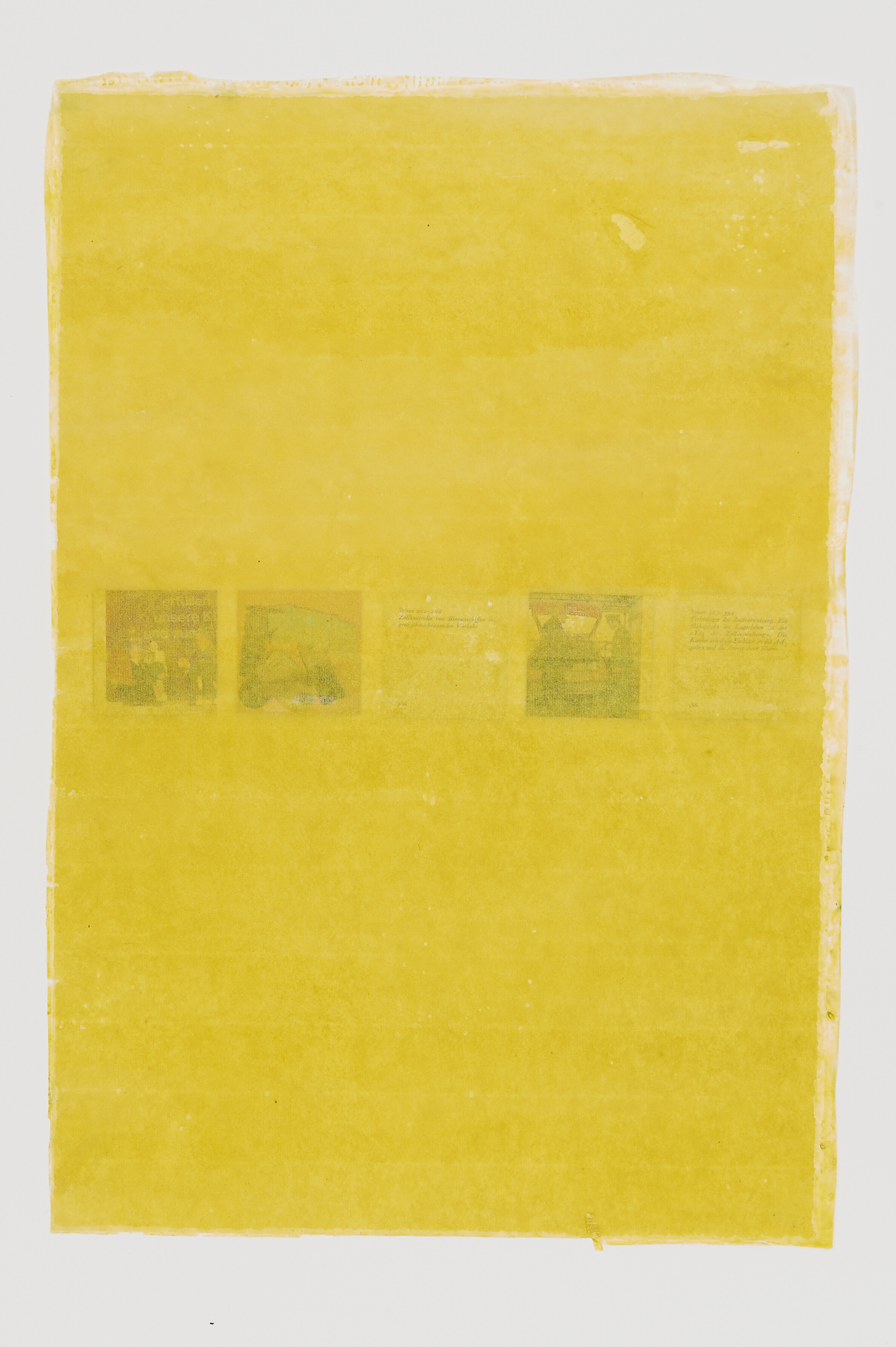

Domestic, Silkscreen, ink, acrylic paint on Strathmore paper, 106 x 94 cm, 2018Domestic, Silkscreen, ink, acrylic paint on Strathmore paper, 106 x 94 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Breakfast Rules, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 61 x 61 cm, 2018Breakfast Rules, Acrylic paint and silkscreen on canvas, 61 x 61 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018

Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018Sports (&) Customs, Handmade Japanese paper treated in a medium solution, watercolor concentrate and ink, page from a novelty DDR book, 44 x 48 cm, 2018