The Porch The Open

Text by Em Rooney

Chris’ particular subjectivity may seem like it has no part in this work, and as his lover, I am in no place to assert objectively that it should. But it just is.

While Chris’ parents were busy working, he spent a lot of time at his grandmother’s house in Valley Forge, PA, where she lived with his aunt. Valley Forge, once home to the starved soldiers of the Continental army during the American Revolutionary war, is a symbol of patriotism in the United States. It was Chris’ backyard. The walls of the house were cluttered with family pictures and the clashing tastes of the two women that lived there; a repressed German Protestant and a retired gay elementary school teacher. Their house, its land, its knick-knacks—have always been an important referent in Chris’ visual lexicon.

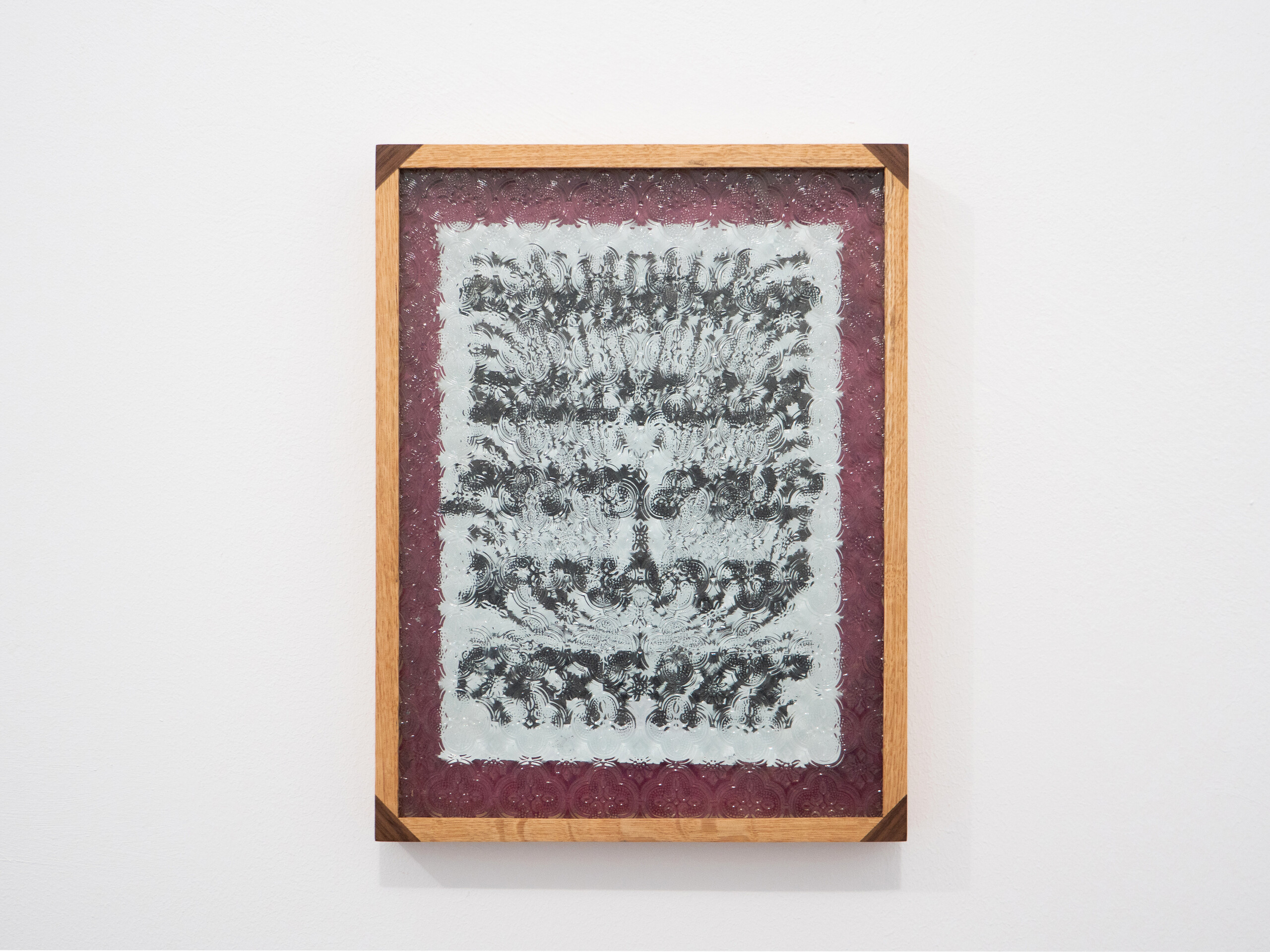

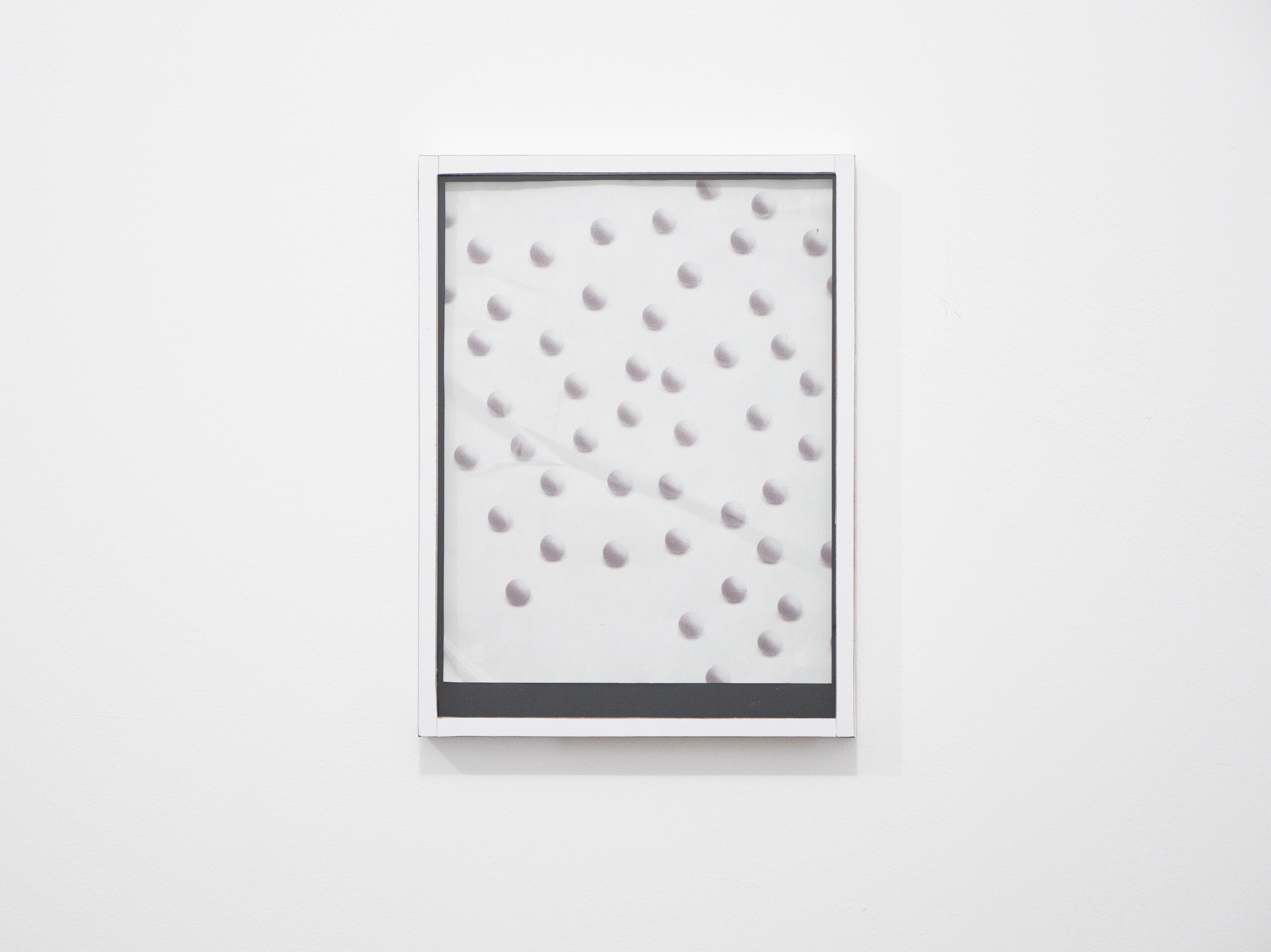

The surfaces, forms and frames of his work create a suture between the exterior and the interior. Fields, roadways, strip malls, and landscapes across America—with all their decrepitude and abstractions — meet the home, where weirder material realities collide. Terry cloth rubs against the leather-grained outer surface of a beige-painted aluminum fridge that has stuck to it (with tape, not a magnet) a moldy love note from six years ago. It was written with a soft leaded pencil and through the graphite marks the scaly texture of the fridge door can be perceived. The note was inadvertently, yet repeatedly, saved.

Chris is an introvert in an introverted job (he takes care of the property we now live on in exchange for free rent). The nine-acre property has five separate structures on it, the first of which was built in 1919 by Gertrude Robinson Smith and Miriam Oliver two society women, lesbians, disowned and determined to make their own “manless Eden” (as it was called in a Boston Sunday Post article published the year they built it). The property is nestled in the foothills of the Berkshires and borders land formerly owned by The Beecher Stowe’s (as in Harriet Beecher Stowe who wrote ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’), and Daniel Chester French (The artist who made the sculpture of Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.). Two-hundred and fifty-year-old trees make a canopy over the house, the woodshop, Chris’ studio, the garden, and the brook that cascades through our property. It is idyllic and historic.

Chris has done so many different types of projects over the years, many of them having to do with the specificity of place— and initially, I think, the Gross Estate, where we live now, may have handed him too much too fast—if an elephant stands two inches away from your face all you see is grey. So this work went through a long evasive period in his imagination. It hummed around his slow movements in the studio, and processed these consumer material relationships—art handling materials, frames as robust or precarious as their contents, laminate, enamel, textured glass, disrupted or broken signage—but had no place. He wondered; “Where is this work located?”

Because Chris grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, once the de facto capital of the US, an area densely populated with bronze placards, low lying houses with plastic siding, as well as mansions (groomed by Chris and his father, a former landscaper), and golf courses (where he caddied)—he is drawn to signifiers we might identify in the latter half of the 20th century, as Americana.

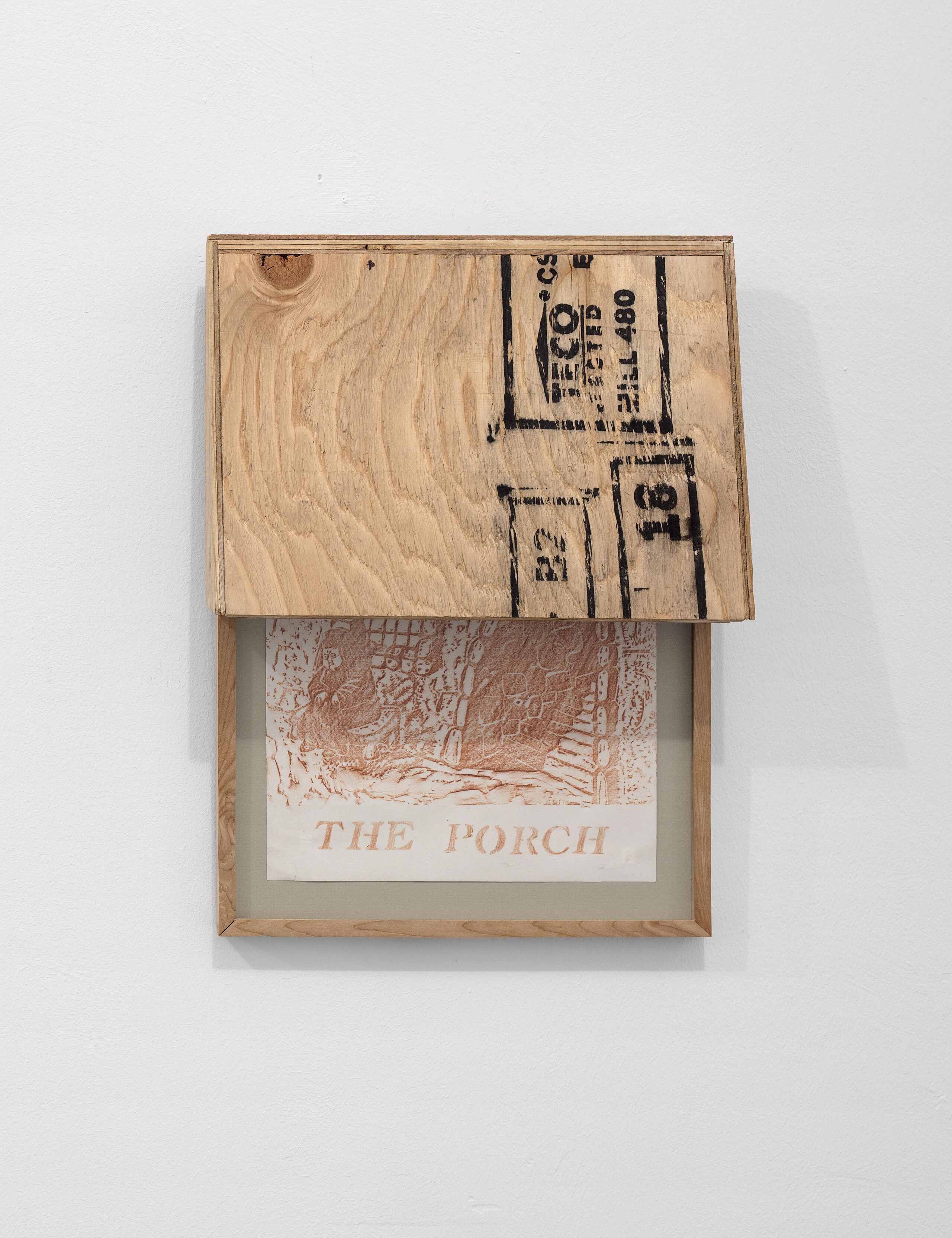

For 10 years he has carried around scrolls of paper and bricks of graphite (a kit we jokingly refer to as “his rubbers”) so that he can make concrete poetry out of historical markers on the side of the road. There are two places in the show where this practice of rubbing comes into play—The first one is in ‘The Magic.’ The other comes from something we found in one of our many cellars, under piles of unused shingles. A linoleum cut plate of an old woman, either a witch or a nun, coming out of a double-doored stone cave— it, mysteriously, reads, like its title, ‘The Porch.’

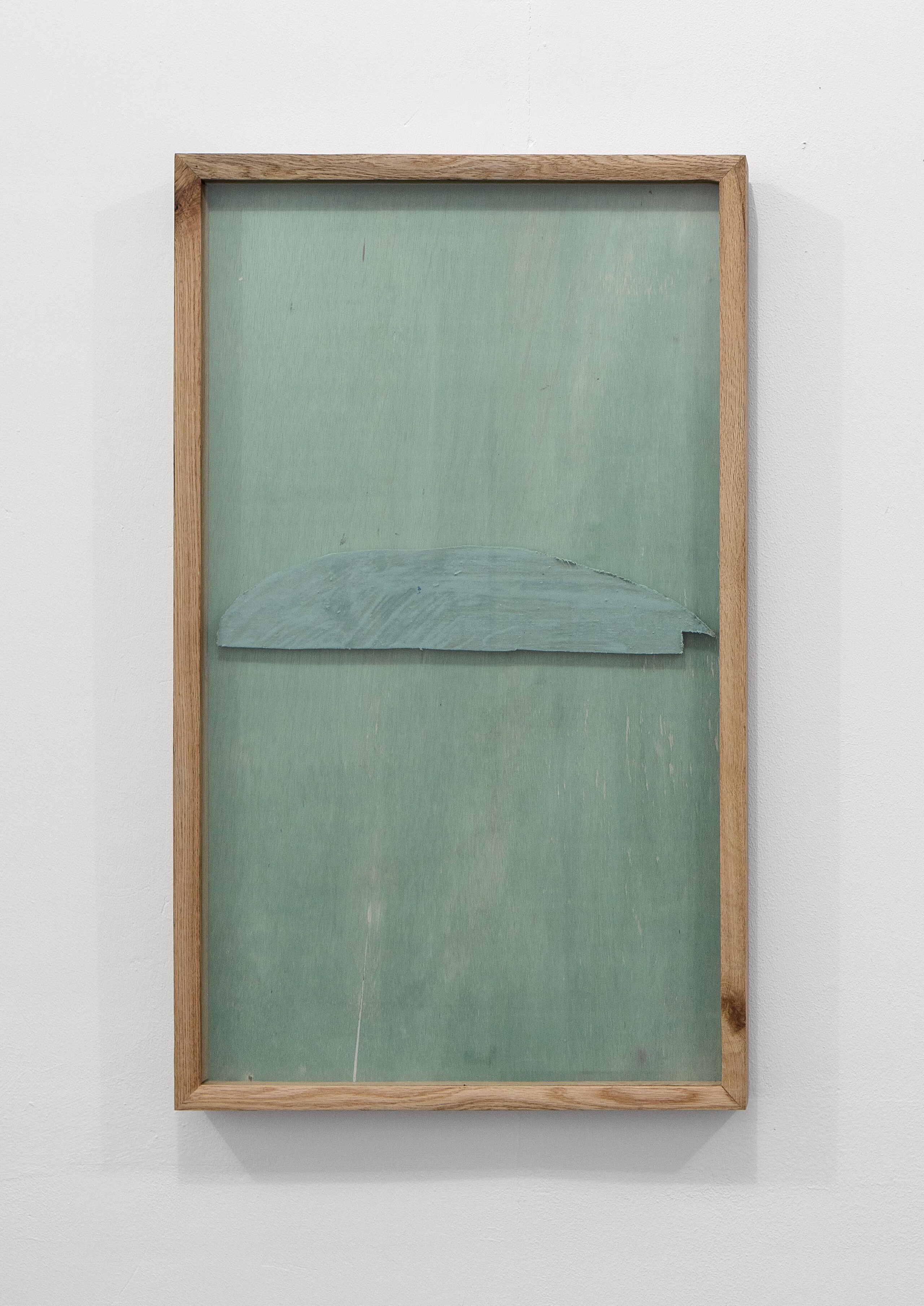

In our current home, where we sit with the ghost of Gertrude, we can see one hundred-year-old screens that need to be replaced, barn doors with peeling paint that need to be patched, a steaming mound of compost in a morning field of lifting fog (everything here is wet), wildflowers everywhere, the huge aching, black sky, and all the buried injustices that allow this place to exist. Beneath the pressure of the surface something is excavated. This work, even the rubbings somehow, begin to entertain the absence of friction. Somewhere between his body, and his surroundings the work is located, in a cloud of sea-green spores.

Chris Domenick (b. 1982, Philadelphia; lives and works in Stockbridge, MA ) received an MFA from Hunter College in 2013 and has participated in residencies including The Shandaken Project, The Sharpe-Walentas Space Program (NY), Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and Recess Activities (NY), among others. Recent projects include Your Shell Is In the Unending, (in collaboration with Em Rooney) at The Beeler Gallery in Columbus, OH, Particulate Paper Records of Time in Cabinet Magazine and 5 O D A Y S at MASS MoCA, Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. He has been included in exhibitions at The Queens Museum, Canada Gallery, The Vanity East, MOMA, Essex Flowers, Situations, Torrance Shipman, Regina Rex, and Room East, among others.