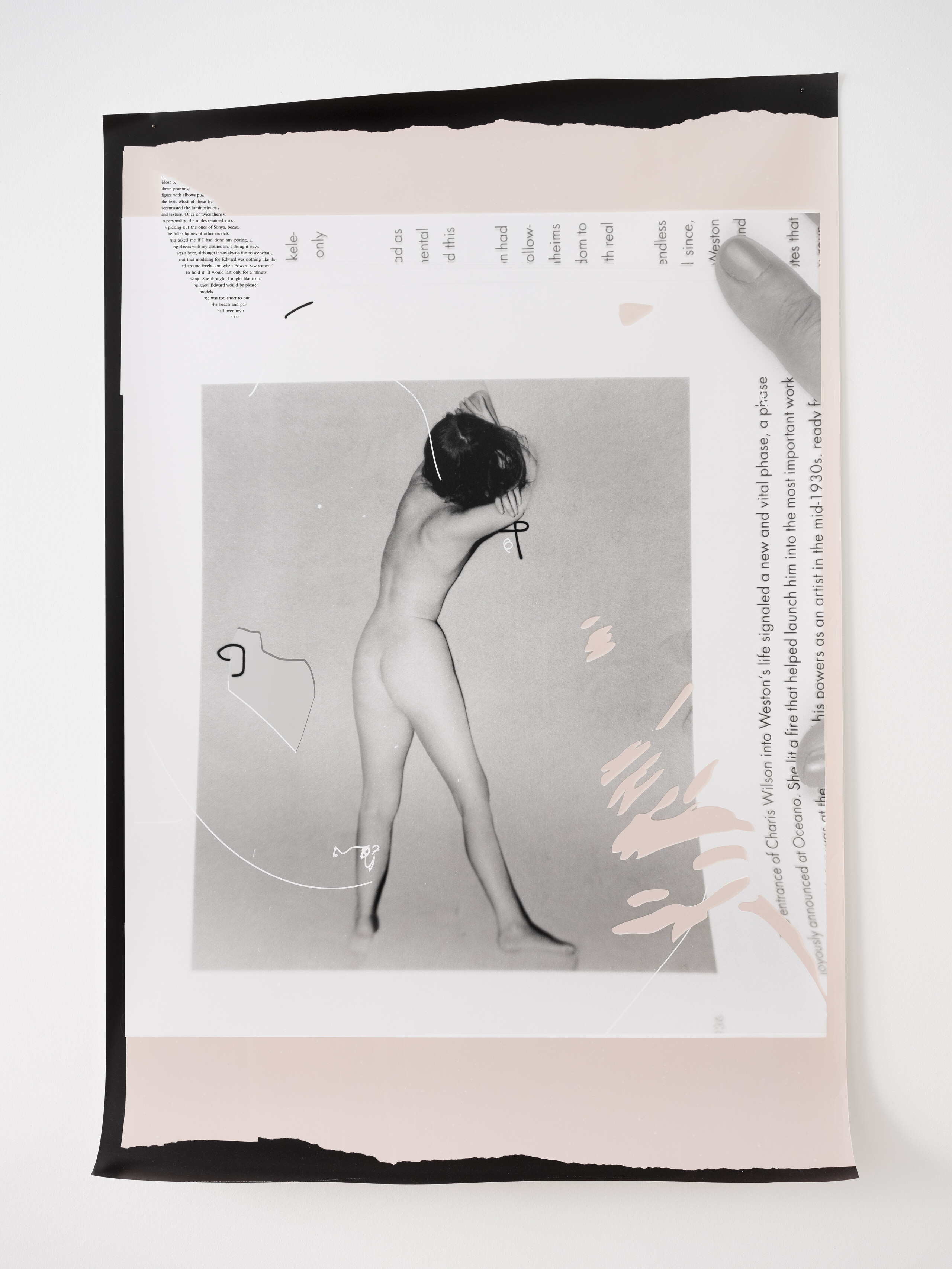

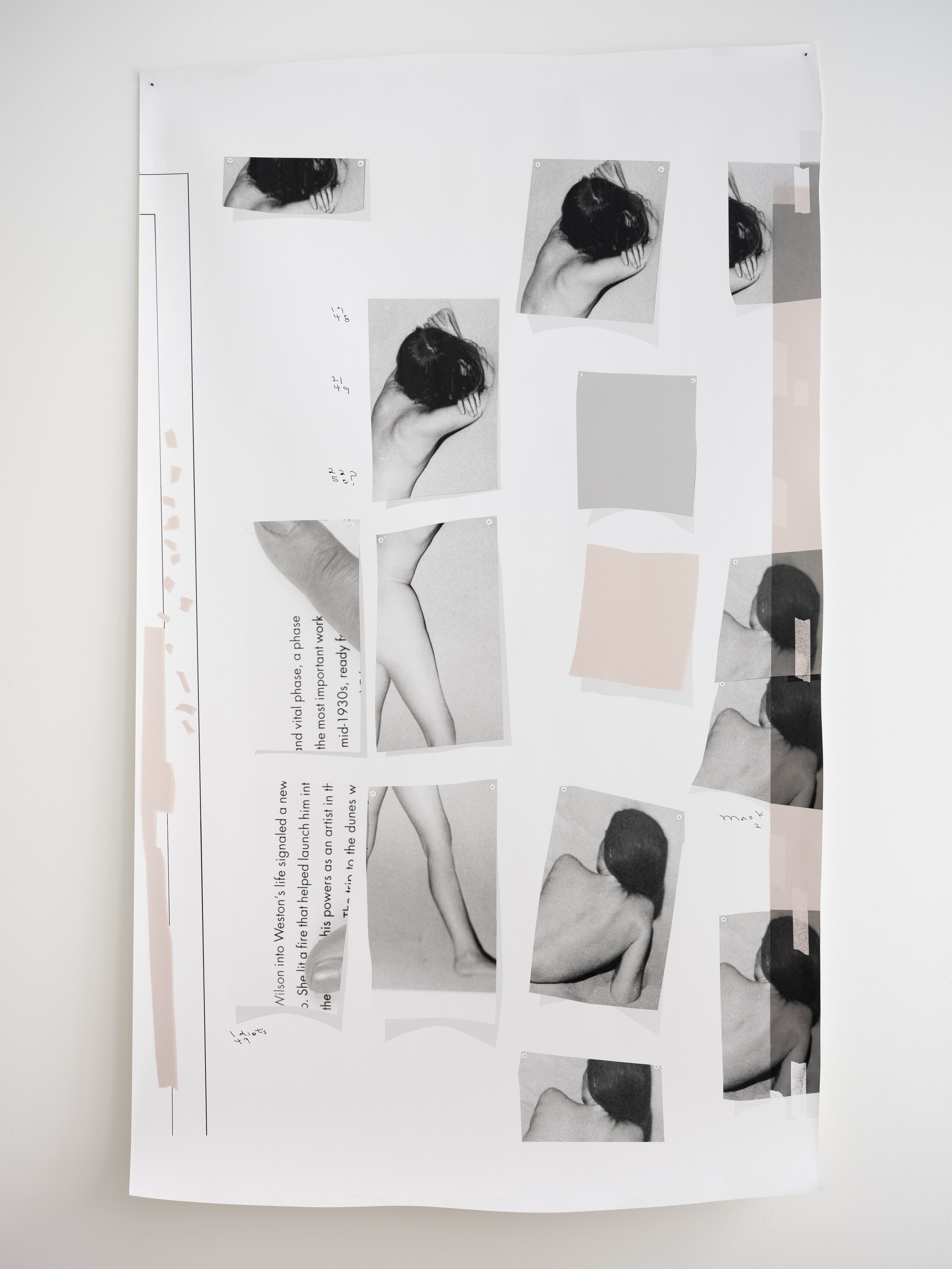

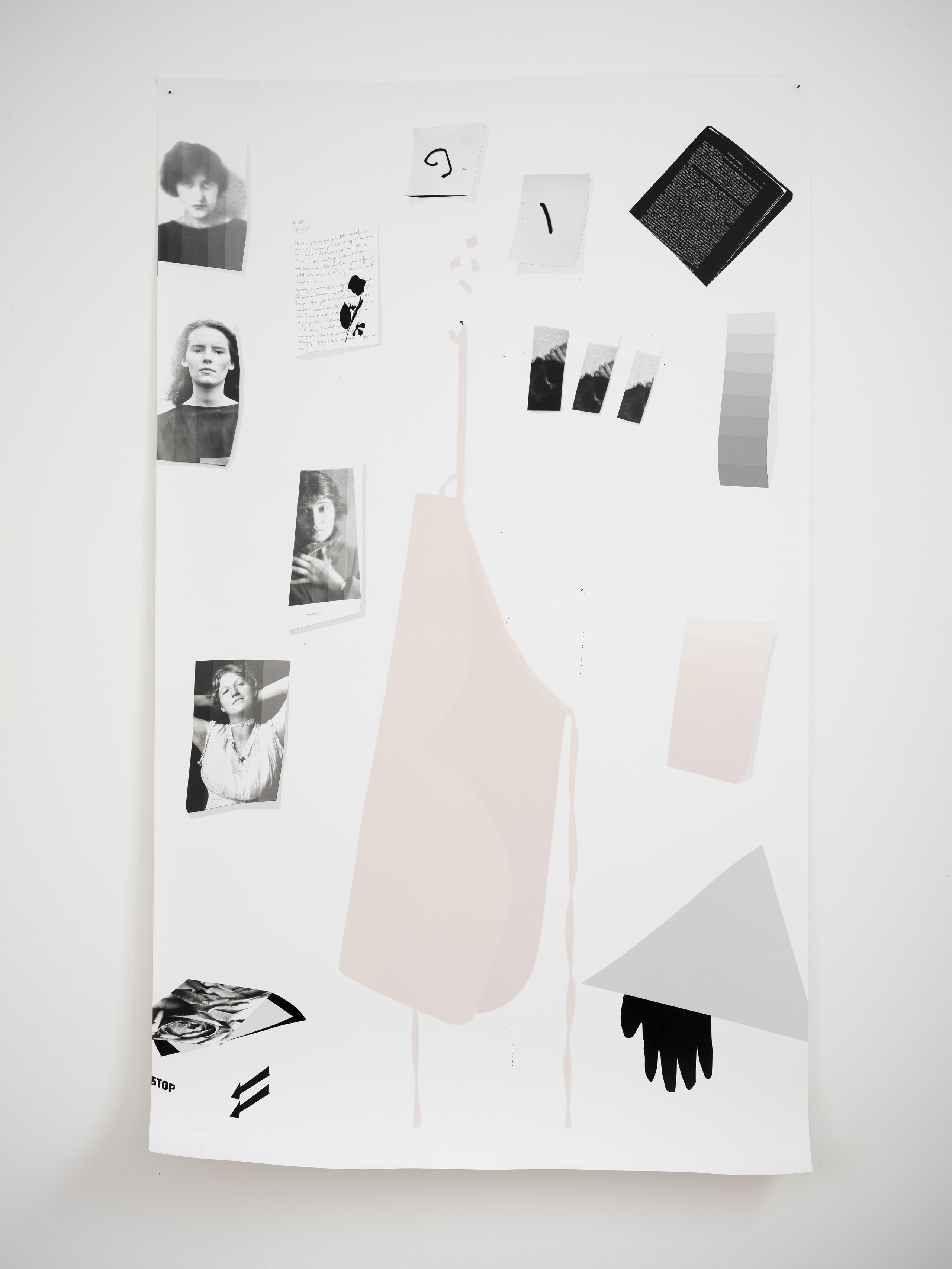

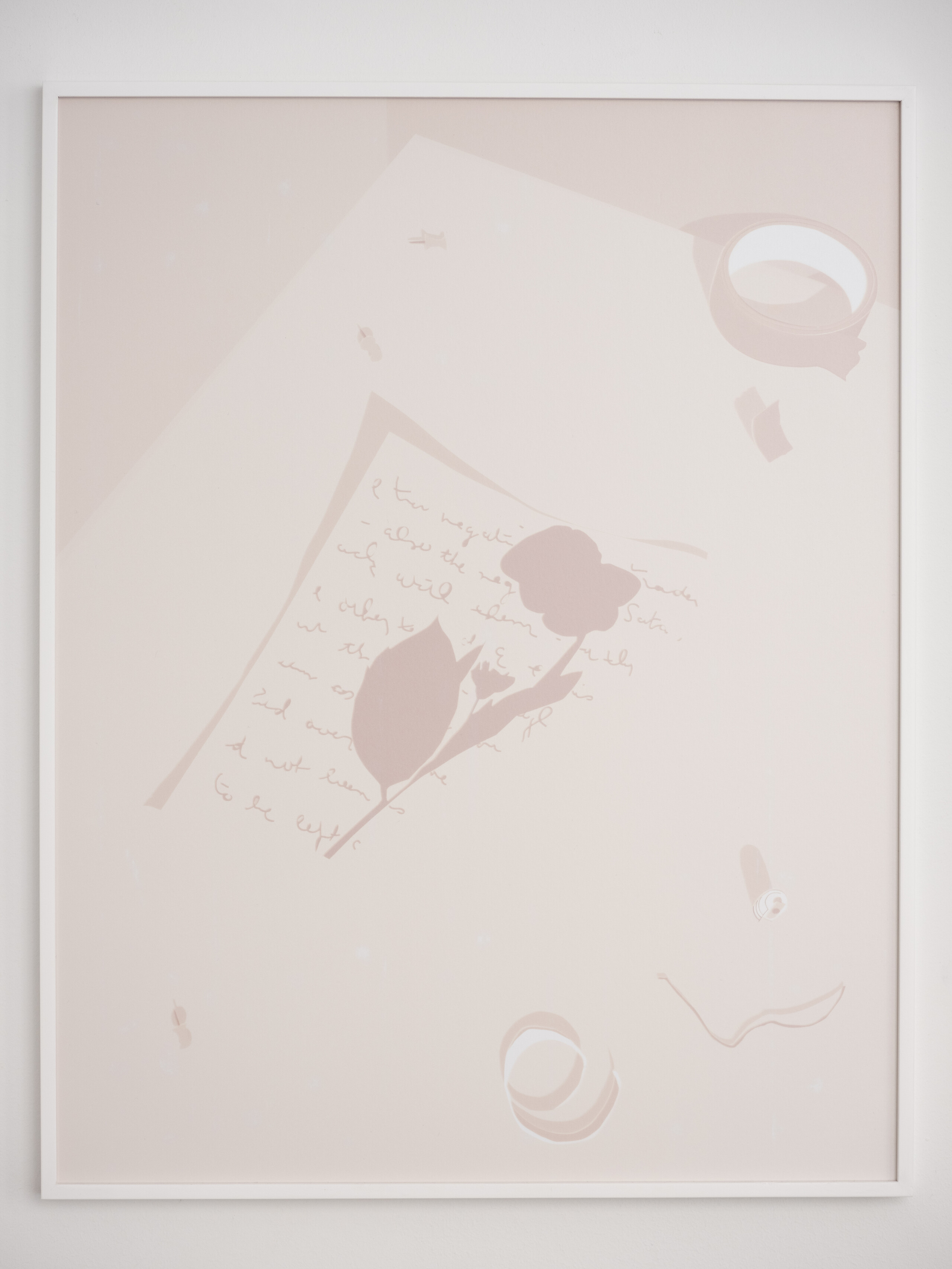

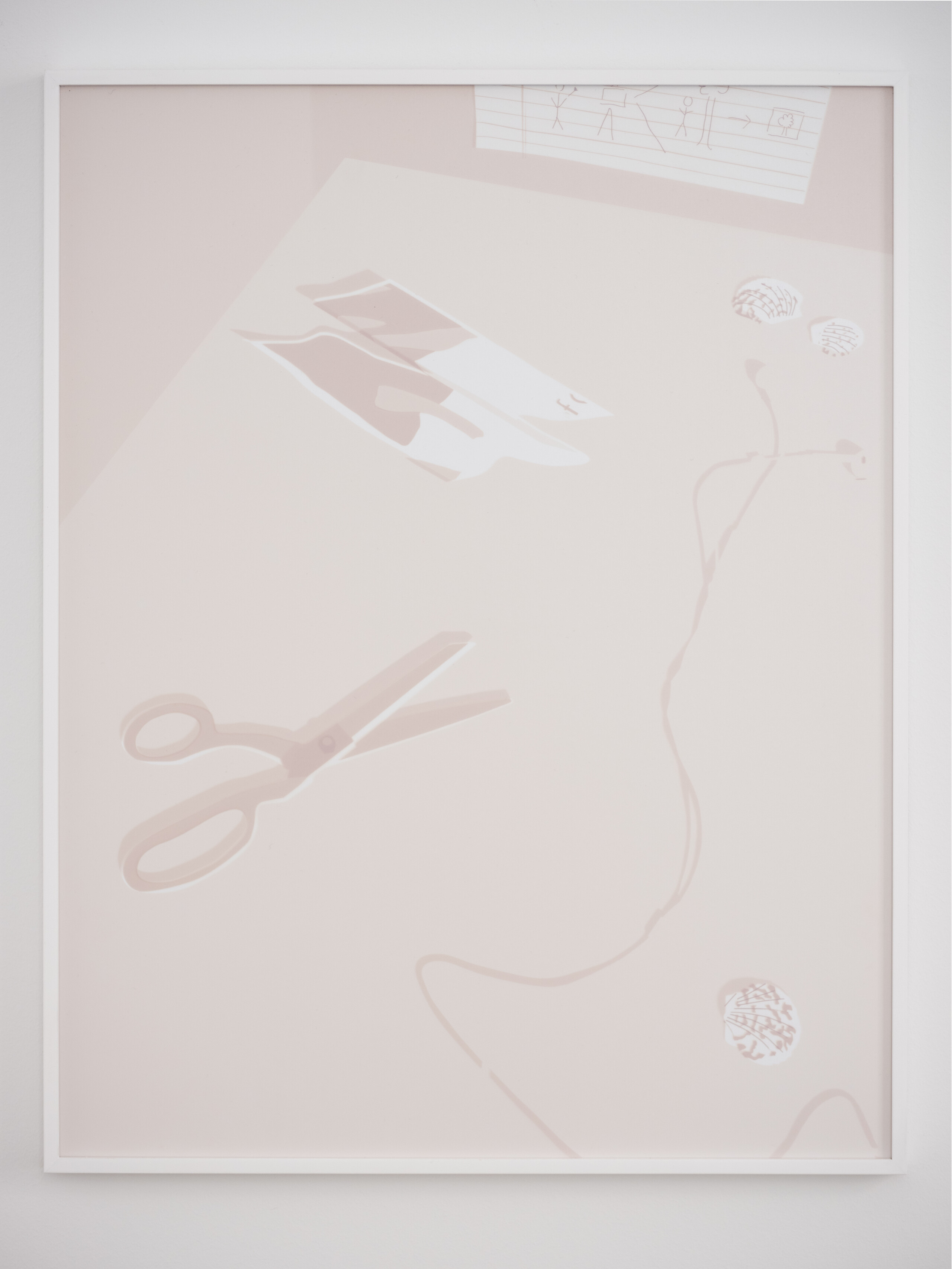

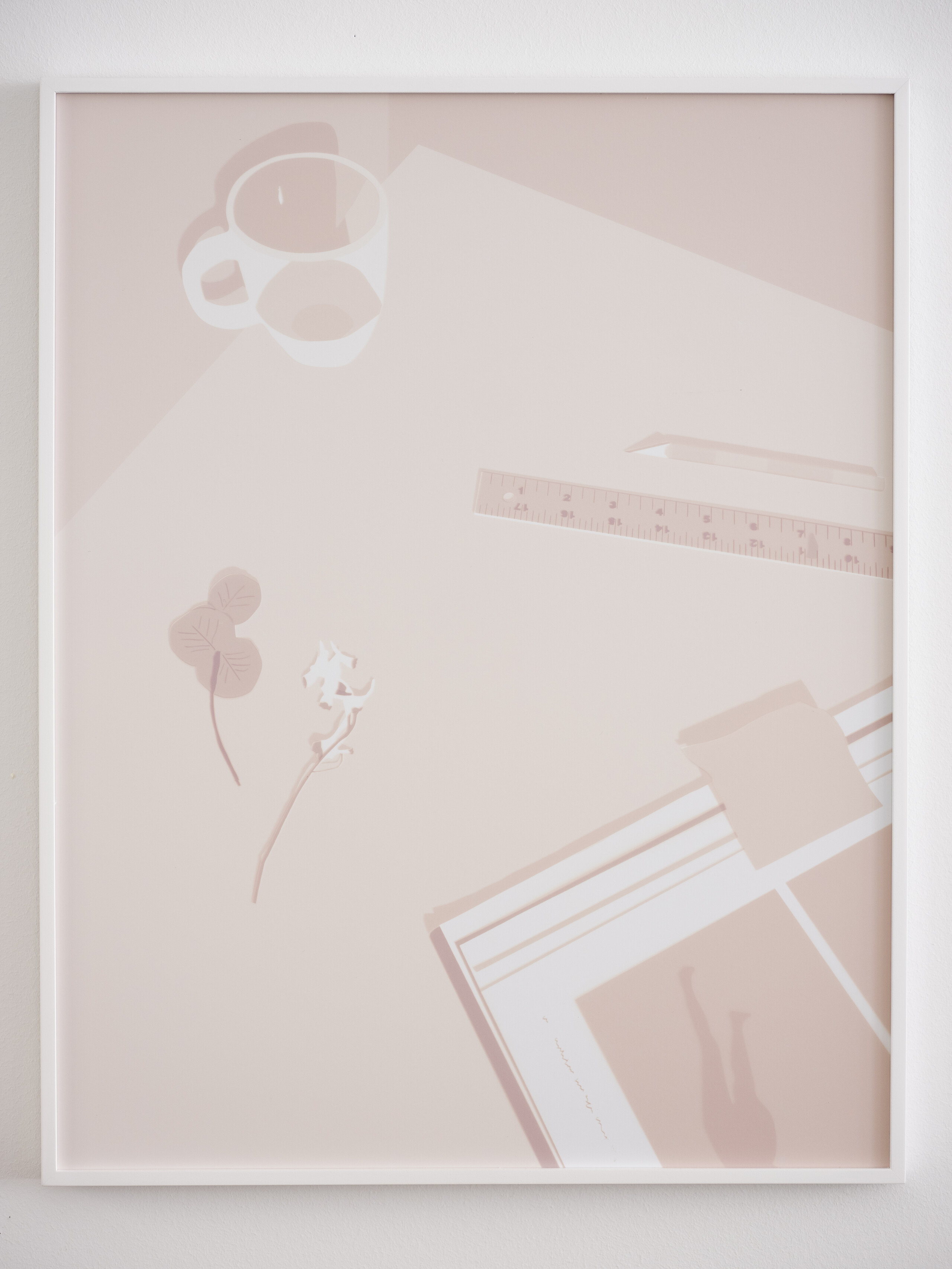

Anthea Behm’s new work utilizes the page, the table, the wall, the gallery, and the chemical photographic print as grounds to explore intersections between her experience as a contemporary artist and the charged dynamics that inflect the canonical photographs that Edward Weston took of Charis Wilson in the 1930’s. Through appropriating some of the pictures Weston made of Charis (his lover, wife, and muse) as well as Wilson’s autobiography, bits of correspondence, and other contextual borrows, Behm mines the layers of the relations that brought these historical pictures into being. In doing so, she is using the contemporary lens to draw attention to considerations of power, abuse and harassment often papered over in the standard histories of photography. Behm has decided on the analogue darkroom’s narrow parameter to make this work. Her pictures, all hand processed analogue silver gelatin prints—made with the aid of physical masks and a ceiling-mounted enlarger—utilize, and in fact expand, the stingy register of the traditional black and white darkroom. They achieve a surprising range of pinks in her black and white prints through subtle manipulation of photography’s standard linear procedures. Behm uses this as a kind of rhetorical conceit, a pressure system that binds the work, creating a new apparatus out of earlier ones: not only Weston’s, but also photography’s more broadly. But Behm’s method also enacts a performance of artistic subjectivity; an all or nothing decision-making that speaks to methodologies of impossible care and to precarity; teaching, illness, legal status, etc. In the darkroom everything is about tolerance and threshold: when a piece of paper has been exposed, when that exposure becomes too much and all goes black, when the chemistry has acted, when the light can be let back in. There is no going back, just beginning again. Laboring in the dark, the artist uses her own body to realize the pictures various fleshy opacities blindly, through touch, experience, and memory. Though unlike almost all work that embraces blind process as its mode, Behm’s work attempts to describe not only her making (think action painting) but also a specific picture—a collection of relationships beyond the marks of process. It is a ritual, a choreographed routine that becomes visible as a picture. As viewers we are left with the material output of Behm’s process and simultaneously with the material of Charis’s relationship to Weston—the gallery feels almost like a studio with tables strewn and notes on the wall. There is a parity achieved between present and past, and we find Behm exposing the relational complexities of the traumatic scene that also contains the means of empowerment, connection, and recovery.

– Lucas Blalock, Brooklyn, NY