A caring hand is not always gentle. It is the founding principle of psychoanalysis (and more recently, affect theory) that tenderness is inextricably linked to, or better, irreparably merged with feelings considered to be its polar opposite. Such inherent ambiguity of care can result in violently possessive episodes (“I care for you, therefore you belong to me”) that tarnish every attempt at its romanticization; yet without care, no ethics is possible.

Niclas Riepshoff’s A Stitch in Time (2021) is an unfaithful replica of a relatively obscure, but also perversely humorous subgenre of kitsch home-decor miniatures that one might purchase on eBay by awkwardly searching for “Grandma Sewing Repairing Upside Down Boy's Pants.” The sculpture is covered with patches of fabric that Riepshoff and his friends have collectively labored over, as in some sort of a para-sewing club. The acts of maintenance, repair, attention—terms that one could liberally subsume under the umbrella term of care—are here shot through with dynamics of submission of domination. The invisibilized domestic labor has a long history of being discredited as unimportant (or more specifically, unproductive) and was thanks to the efforts of second-wave feminism turned away from its almost-biological naturalization into a crucial site of contestation. The enlarged figurine transforms the supposedly enjoyable pastime of maintenance into something more threatening, perhaps even vengeful. Importantly, within the oscillation between holding and pulling, the depicted matriarch’s ambivalently caring attitude towards her progeny is also an educational gesture, a thoughtful instance of giving shape to not only something but someone, through manual labor.

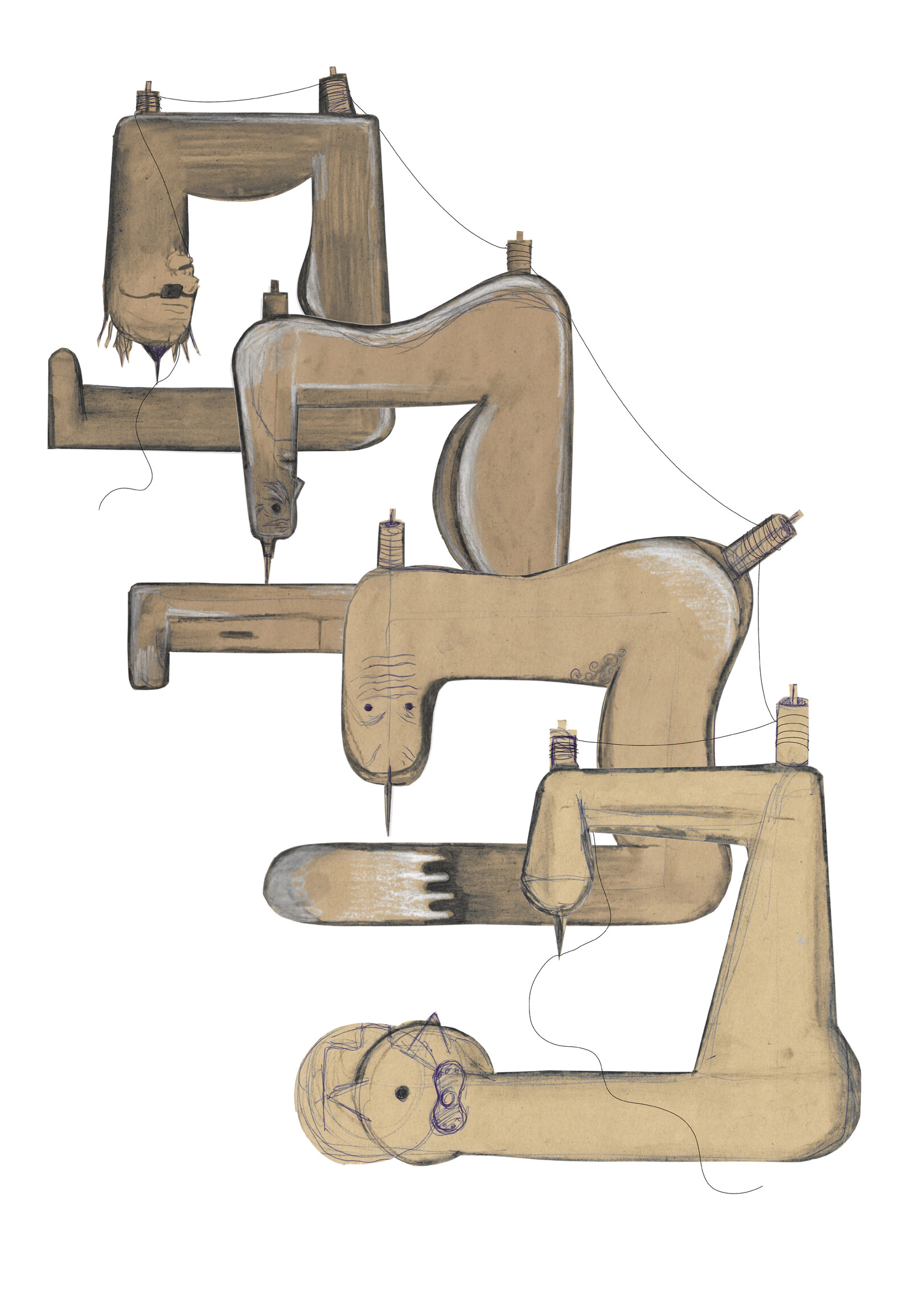

Analogies between sewing and character molding likewise abound in the series Threaders (2021), where Riepshoff depicts a handful of his former teachers on the needle threader-shaped support, each one of them having exerted a specific influence in the artist’s past lives. In this visual bildungsroman, the pedagogues pose with a needle and threads, wielding them as weapons of intergenerational transmission of knowledge and skill. If one of the paradigmatic qualities of our neoliberal age is a (false) glorification of non-hierarchies and the conflation of authority with authoritarianism, the teachers are here iconized and granted an almost assertive monopoly over a specific area of expertise: English, maths, astronomy, painting and even kindergarten education. But sewing, today’s unsung victim of automatization is—like any other technology—an externalization of one’s self that recursively feeds back into the user/maker, continuously influencing their decisions. In cases of good education, such molding of students is therefore never unidirectional. Instead, a teacher is taught while teaching, becoming prone to external influences, willing to listen. In short, they are receptive (in Riepshoff’s portraits the aura of mastery is occasionally contaminated with limp wrists, a quintessential example of gay semiotics). A fruitful pedagogical authority is willing to de-privatize the skills, instead of hoarding them and banishing them to some inaccessible vault. The very choice of the needle threader—a helping device, usually reduced to the shameful status of a mere auxiliary tool—might tell us that perceptive educators will help students become better people within the scope of their own, of course never purely individual, means.

Craft is arguably always already feminized, the little sister to her masculine brother, fine arts. With the bourgeois predilection for uselessness and detached contemplation, art became superior to what was considered mere manual labor, devoid of intellectual prestige. These binaries are heavily encoded in the history of art (or better, in a history of aesthetic expression) and authors like Julia Bryan-Wilson, Rozsika Parker, and Joseph McBrinn remind us that while sewing and other textile techniques have since the Victorian era been directly related to female subservience, they have also provided for a creative outlet where links between women (and gay men) could be built. Although such historical connotations might be waning within the enclave of contemporary art, in Riepshoff’s exhibition, the artisanal skill features not only as a form, but as a medium where the just-mentioned genealogical baggage is not only impossible to do away with, but is explicitly accommodated for.

Text by Sebastjan Brank

Publication

Who is a Good Boi?

Design: JMMP – Julian Mader, Max Prediger

The exhibition is supported by

Stiftung Kunstfonds

Neustart Kultur