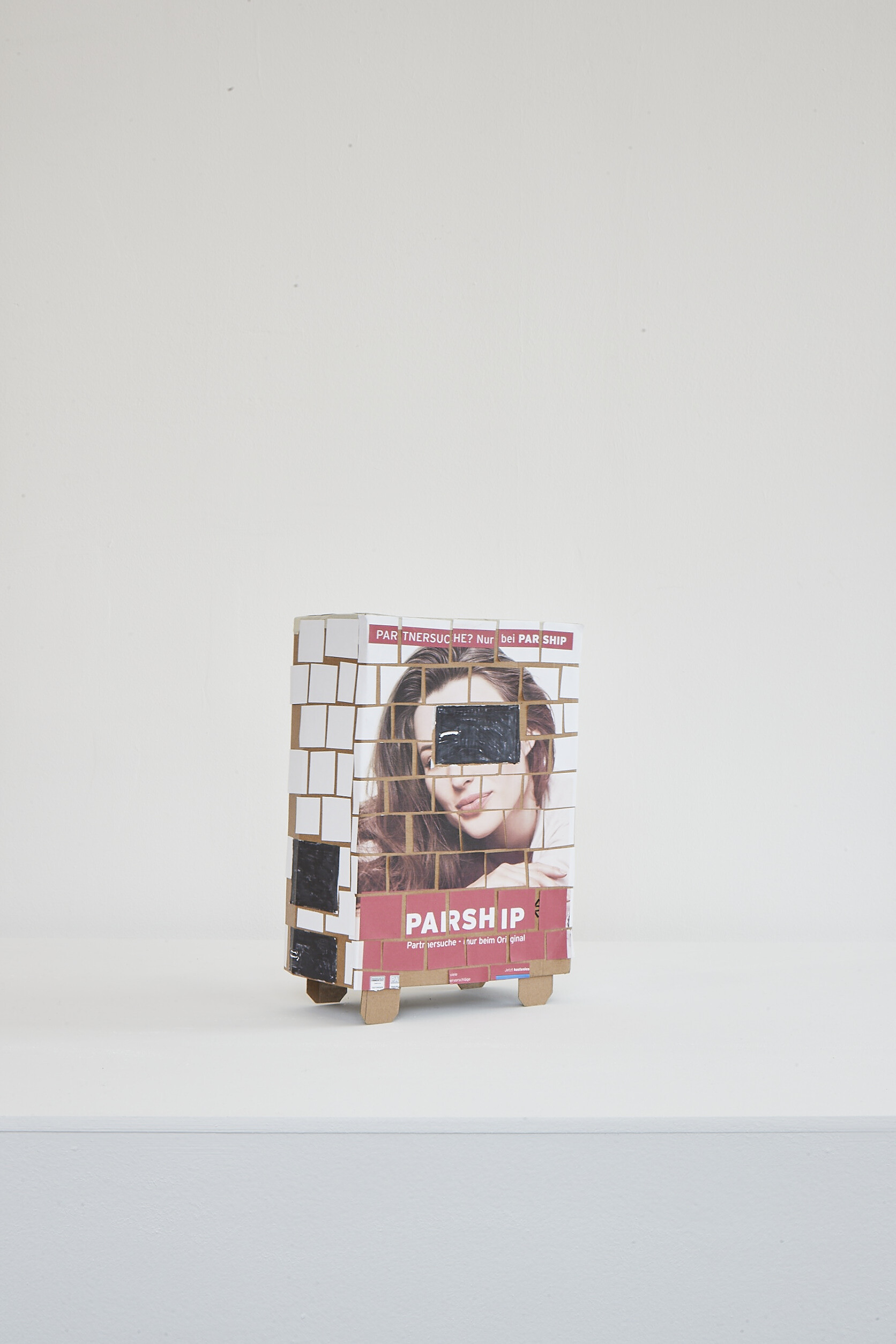

Niclas Riepshoff’s Berliner Öfen are reminiscent of traditional Old World ceramic ovens (in german, Kachelöfen), found throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Big and clunky, yet beautiful and elegant, they are finely crafted emblems of cultural identity. Fueled by coal, these hulking, tiled masses would radiate heat during the last century, bringing delight to anyone who longed for their pleasant warmth. With the rise of more convenient radiators and Germany’s plan to become greenhouse gas-neutral by 2050, home owners who were transported back to the past merely by looking at the tiled ovens, were required to retrofit their ovens with a filter in order to reduce pollution and carbon dioxide emissions. Today, these nostalgic polluters have become more than just heaters. They have been turned into objects of desire in one of the worlds hottest housing markets. They are ornaments, which adorn apartments, independent sculptures or mimicries that integrate themselves into the interior. Looking at rents in Berlin, which have skyrocketed due to exploding demand and increased speculation, Riepshoff addresses the urgency faced by tenants in neighbourhoods becoming so gentrified that they can no longer afford the rising rents and are forced to move outside of the capital. Unlike the original tiled ovens, Riepshoff’s ovens are much smaller, which emphasises the ovens sculptural identity. Some stand alone while others are grouped together – like a family. Family, a single word with many different meanings. The traditional make up of a family consists of a mother and father, married and raising their biological children in one household. Fast forward to present day, you’ll find that families come in all different forms, allowing people to define family for themselves. What counts are not the specific structures but the extent to which they are connected to one another. What holds a family together? Biological relationships? Love and support? Sharing the same home? These questions are raised and expressed by Riepshoff through the pairing of the warm miniature-ovens that reflect the multiplicity of familial compositions. In a way, the traditional definition of the ‘nuclear family’ has become a relic of bygone times just like the tiled ovens. ‘Nuclear’ means ‘the core’ and the family core is the heart of the family. For children, it’s usually the parents. The nucleus of the home has for a long time been the tiled oven, which gathers and protects your loved ones. Riepshoff himself doesn’t have any children and has a rather ambivalent attitude towards fatherhood. As a gay man it’s not impossible to start a family, but until today the decision to do so will call for logistical issues, legal hurdles and financial obstacles. Adoption, foster care or assisted reproductive technologies are all options for having children. In vitro fertilisation is one way to conceive children - and one in which Riepshoff takes particular interest. In In Vitro (2020) Riepshoff depicts the moment of artificial fertilization by interpreting the design of the classic Wilhelm Wagenfeld lamp as a steel cannula entering the vitreous ovum, injecting LED sperm. Read in the context of the mentioned works, the exhibition raises questions about parenthood and emphasises the increased opportunities for couples to parent by addressing reproduction and infant hood.